The 298th Block: RISJ's journalism prediction, an untouchable hacker god, and the foreign nationals lured into the Russian army

Also, Wikipedia is 25!

This week…

Your reading time is about 5 minutes. Let’s start.

Not to be a fangirl or anything but…

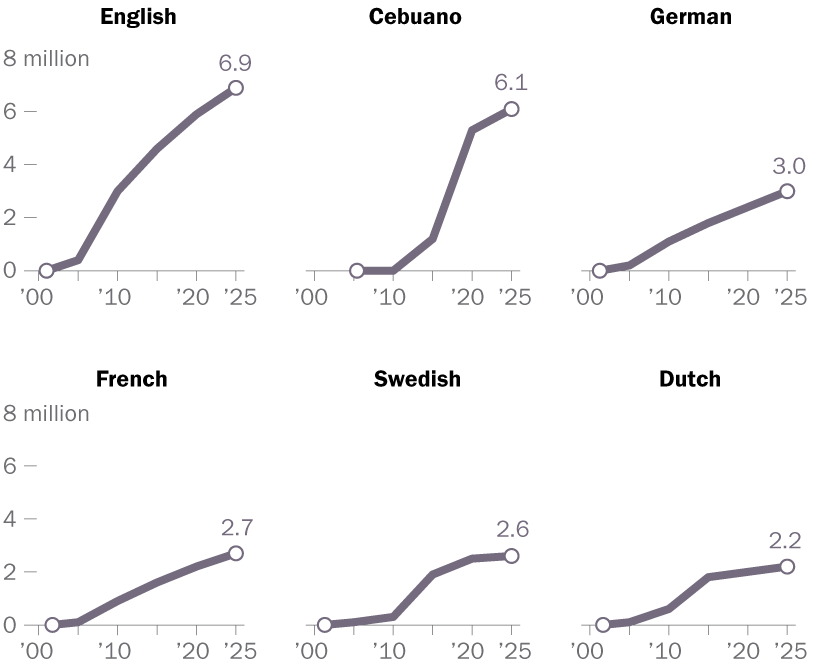

Wikipedia celebrated its 25th anniversary on Thursday, January 15th. It’s hard to imagine the internet without Wikipedia, tbh. With more than 65 million articies across more than 300 languages, Wikipedia is edited by nearly 250,000 volunteers every month!

You can peek into the lives of some of Wikipedia’s editors here. And if you’re still in your online quiz era, you can also find out ‘Which Wikipedia of the future are you?’ I am the ‘The Consensus-Driven Collaborator’ lol.

Your Wikipedia this week: Criticism of Wikipedia

And now, a selection of top stories on my radar, a few personal recommendations, and the chart of the week.

ICYMI: The Previous Block was about the information blockade in Venezuela, facial recognition in India, and digital citizen socre in Vietnam.

CORRECTION NOTICE: None notified. DISINFORMATION, MEDIA & JOURNALISM

Journalism, media, and technology trends and predictions 2026

Nic Newman for RISJ:

Existential challenges abound. Declining engagement for traditional media combined with low trust is leading many politicians, businessmen, and celebrities to conclude that they can bypass the media entirely, giving interviews instead to sympathetic podcasters or YouTubers. This Trump 2.0 playbook – now widely copied around the world – often comes bundled with a barrage of intimidating legal threats against publishers and continuing attempts to undermine trust by branding independent media and individual journalists as ‘fake news’. These narratives are finding fertile ground with audiences – especially younger ones – that prefer the convenience of accessing news from platforms, and have weaker connections with traditional news brands. Meanwhile search engines are turning into AI-driven answer engines, where content is surfaced in chat windows, raising fears that referral traffic for publishers could dry up, undermining existing and future business models.

Despite these difficulties many traditional news organisations remain optimistic about their own business – if not about journalism itself. Publishers will be focused this year on re-engineering their businesses for the age of AI, with more distinctive content and a more human face. They will also be looking beyond the article, investing more in multiple formats especially video and adjusting their content to make it more ‘liquid’ and therefore easier to reformat and personalise. At the same time, they’ll be continuing to work out how best to use Generative AI themselves across newsgathering, packaging, and distribution. It’s a delicate balancing act but one that – if they can pull it off – holds out the promise of greater efficiency and more relevant and engaging journalism.

Loosely linked:

For Venezuelan journalists, it’s like Maduro never left by Caroline Abbott Galvão and Ivan L. Nagy for CJR.

How Russia’s new takes on censorship challenge the work of journalists by Veronica Snoj for The Fix.

Study links limited press freedom to higher use of access to information laws in Latin America by César López Linares for LJR.

Why do educated people fall for conspiracy theories? It could be narcissism by Tylor Cosgrove (Adelaide University) for The Conversation.

Un lugar seguro para que las gazatíes puedan seguir siendo periodistas por Beatriz Lecumberri (texto) y Shoroq Shaheen (fotos) en El País.

Comment savoir si une image est authentique ? La réponse des agences de presse face à la menace de l’IA par Marius Joly dans La revue des médias.

DATA, AI & BIG TECH

He called himself an ‘untouchable hacker god’. But who was behind the biggest crime Finland has ever known?

Jenny Kleeman for The Guardian:

Tiina Parikka was half-naked when she read the email. It was a Saturday in late October 2020, and Parikka had spent the morning sorting out plans for distance learning after a Covid outbreak at the school where she was headteacher. She had taken a sauna at her flat in Vantaa, just outside Finland’s capital, Helsinki, and when she came into her bedroom to get dressed, she idly checked her phone. There was a message that began with Parikka’s name and her social security number – the unique code used to identify Finnish people when they access healthcare, education and banking. “I knew then that this is not a game,” she says.

The email was in Finnish. It was jarringly polite. “We are contacting you because you have used Vastaamo’s therapy and/or psychiatric services,” it read. “Unfortunately, we have to ask you to pay to keep your personal information safe.” The sender demanded €200 in bitcoin within 24 hours, otherwise the price would go up to €500 within 48 hours. “If we still do not receive our money after this, your information will be published for everyone to see, including your name, address, phone number, social security number and detailed records containing transcripts of your conversations with Vastaamo’s therapists or psychiatrists.”

Parikka swallows hard as she relives this memory. “My heart was pounding. It was really difficult to breathe. I remember lying down on the bed and telling my spouse, ‘I think I’m going to have a heart attack.’”

Someone had hacked into Vastaamo, the company through which Parikka had accessed psychotherapy. They’d got hold of therapy notes containing her most private, intimate feelings and darkest thoughts – and they were holding them to ransom. Parikka’s mind raced as she tried to recall everything she’d confided during three years of weekly therapy sessions. How would her family react if they knew what she’d been saying? What would her students say? The sense of exposure and violation was unfathomable: “It felt like a public rape.”

Loosely linked:

Grok’s biggest danger isn’t what it says — it’s where it lives by Damilare Dosunmu for Rest of World.

Why India’s plan to make AI companies pay for training data should go global by Javaid Iqbal Sofi for Rest of World.

Kenya’s health data deal with the US: What the agreement gets right and what it misses by Shirley A. Genga (Free State Centre for Human Rights) for JURIST.

An app’s blunt life check adds another layer to the loneliness crisis in China by Ted Anthony and Fu Ting for AP.

Sienna Rose: The mysterious singer with millions of streams — but who (or what) is she? by Mark Savage for BBC.

Qué revela el caso de los deepfakes en Grok sobre la violencia digital contra las mujeres: “La desprotección es gigantesca” por Andrew Proenza en elDario.es.

Relations parasociales : face à l’IA, l’humain va-t-il choisir le vide ou la vie ? par Blaise Mao dans Usbek & Rica.

DEMOCRACY, RIGHTS & REGULATION

‘I made the biggest mistake’: the young Yemeni men lured into the Russian army with empty promises

Nawal Al Maghafi for The Guardian:

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has dragged on into a fourth year, and its appetite for manpower is relentless. An estimated 20,000 foreign fighters have been pulled in from across the world, from countries including Nepal, Cuba, South Africa and North Korea, in what is being advertised as ideological “volunteering” but is, in reality, recruitment by exploitation.

Back in March 2022, President Vladimir Putin publicly backed the idea of bringing men from the Middle East to fight, insisting they wanted to come “not for money”, and that Russia should help them reach the combat zone. What I have seen since is a pipeline: informal brokers and online channels connecting desperate men to contracts with Russia’s military. These contracts often promise a year, a salary, a passport, and safety, but the fine print can trap them indefinitely.

I began following the stories of Yemeni recruits after videos started circulating online: young men filming themselves from Russia, pleading for help. One of them, his voice cracking, says: “We die a thousand times a day from the terror we endure at the hands of the Russians … save your Yemeni brothers … we are being forced to fight … our friends are dead … we are trapped between life and death.”

The videos were raw, immediate, and hard to watch.

See the BBC doc in the section below. Loosely linked:

Russia lost Venezuela. Putin won everything else by Natalia Antelava for Coda.

Yoweri Museveni: He once criticised African leaders who cling to power. Now he’s won a seventh term by Wedaeli Chibelushi for BBC.

Greenland: new shipping routes, hidden minerals – and a frontline between the US and Russia by Ashley Kirk, Lucy Swan, Tural Ahmedzade, Harvey Symons and Oliver Holmes for The Guardian.

Iran in limbo: What’s next for country under internet blackout? by Maziar Motamedi for Al Jazeera.

As hate spirals in India, Hindu extremists turn to Christian targets by Kunal Puroit for Al Jazeera.

Los refugiados sirios, un año después de la caída de Al-Assad por Ana López García en CTXT.

Comment des groupes d’extrême droite radicale utilisent les combats clandestins ultra-violents de free-fight pour faire leur pub par C. Guttin, B. Mingot, A. Dupas dans Franceinfo.

What I read, listen, and watch

I’m reading Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race that Will Change the World (2024) by Parmy Olson. A little bit of history of the rivalry between the biggest AI firms — mainly OpenAI and DeepMind. You know, Altman vs. Hassabis, a little of China, too. And Musk, of course.

I’m listening to a Conspirituality episode on the AI orientalism of Yang Mun a Buddhist ‘monk’ created by Israeli tech bros.

I’m watching BBC’s documentary on Russia’s recruitment of foreign nationals as frontline soldiers for its Ukraine invasion.

Chart of the week

Pew Research Center answers some common questions about Wikipedia based on data from the site. One interesting chart shows that while English is still the most common language on Wikipedia, bots have boosted content in Swedish and Cebuano, thanks to Lsjbot.