Create, curate and arbitrate influence

Cristina Tardáguila for Poynter: Without methodology or transparency, Facebook and Twitter become the ‘arbiters of the truth’.

Emily Bell and Sara Sheridan for CJR: Google and Facebook have a news labelling problem.

Amelia Tait for The Guardian: Influencers are turning to unions.

Stephen Gossett for Builtin: The Internet should be more like Wikipedia.

Dude, where’s my nude?

[Image censored jk – I have a busy week this week]

Remember tech journalist Charles Arthur? I had one short interview with him in 2019, and I haven’t come close to sharing every single gem that came out of his mouth:

In the days before the Internet, when you relied on printed newspapers, radio, [and] TV, there were, in fact, gatekeepers. There were the people who produce the TV shows, radio shows, editors of the newspapers – they decide what was shown and so there was a gatekeeper function which kept anonymous views, unsupported views out of public discourse because the question was, well, who are you and why are you saying this?

But with social networks, it doesn’t matter who you are. You can just put things [online] and if they get picked up and if they go viral, then nobody cares who the creator is. They’re just interested in what the content is. So anonymity doesn’t make any difference to the “quality” or the level of interest in a piece of work. News [becomes] stuff I care about, stuff I want to pass on. And nowhere in that does it say that you have to care about who produce the content.

Online, user-generated contents do not have these so-called gatekeepers – or editors. Editors, traditionally, decide whether or not to publish a story. They ensure the credibility and quality of the content. They also decide the relative order of importance of different news pieces. These aren’t decided by popularity or profit.

But for social media platforms, story visibility is decided precisely by popularity and profit. They become news editors without actually taking up the responsibilities of editing. And if you argue that it’s not possible to moderate content, then consider this: Why is it so difficult to find nudes on Facebook or Instagram?

What I read, watch and listen to…

I’m reading why social media makes me feel so old.

I’m watching Ann Reardon explain Australia’s news media bargaining code (starts at 14:54 until 22:22).

TL;DR: Australia is trying to make Big Tech pay for the news. Big Tech says they are just bus drivers taking passengers (users) to the restaurants (news), so they shouldn’t be paying the restaurants, the passengers should be. But Reardon demonstrates that passengers can still sample restaurant food on the bus without ever leaving it.

Try it yourself: Look up the weather, and you get the information you need on the google.com domain without ever visiting the site weather.com, where the information is taken from. Look up COVID-19 stats, and your search results, still on the google.com domain, show the latest data, that’s sourced from The New York Times.

I’m listening to Dewa Risqullah’s powerful spoken-word piece on Indonesia’s protest against the country’s new labour law.

Chart of the week

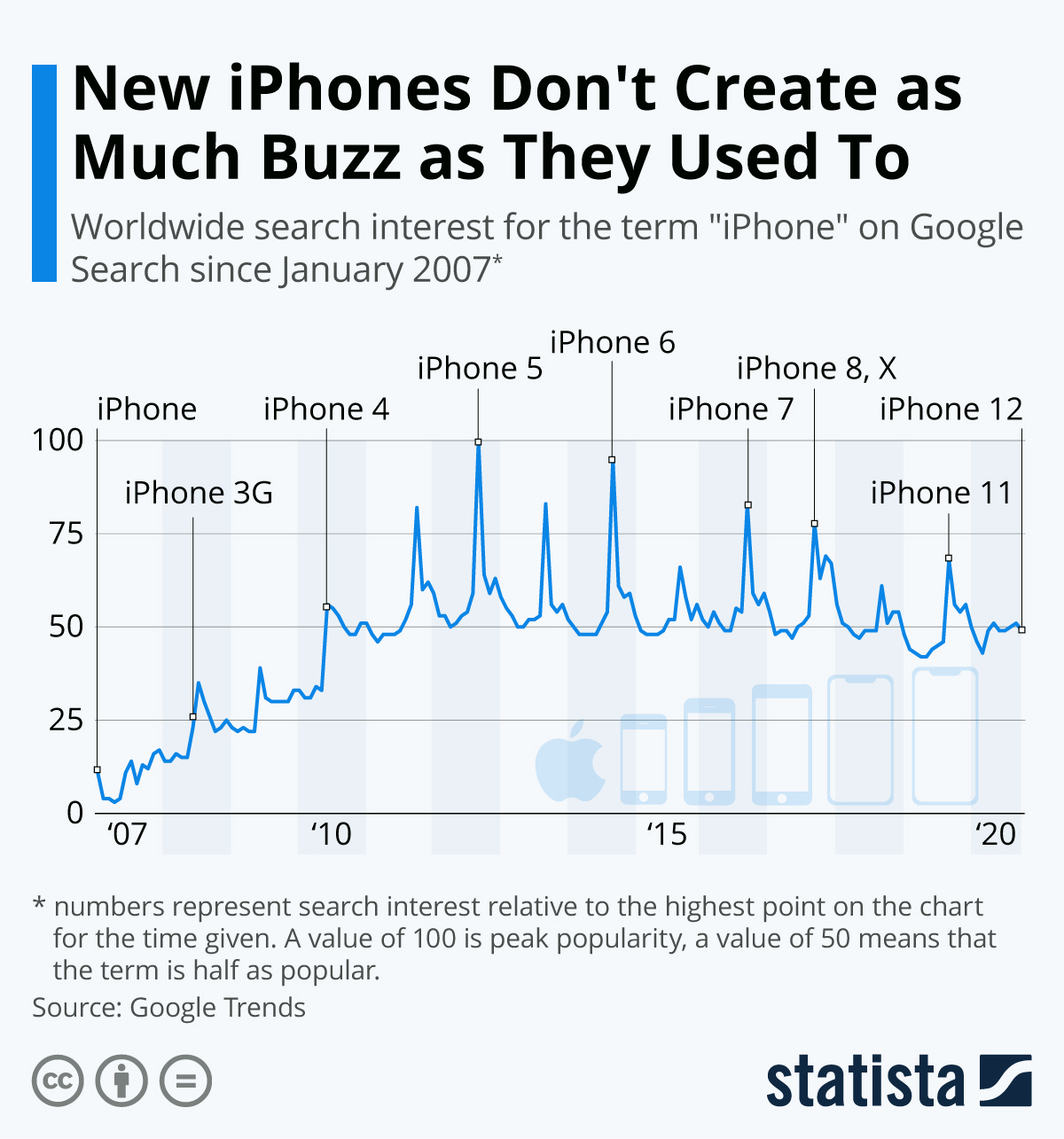

From Statista: New iPhones don’t create as much buzz as they used to. Also related stats, the iPhone index – an American minimum wage worker has to work 24 days to buy the new iPhone 12 Pro Max 512GB, and 5.5 months for a Malaysian minimum wage worker.

Fakta, Auta & Data #10: DBP, apakah istilah rasmi untuk ‘content moderation’?

Masih ingat wartawan teknologi, Charles Arthur? Saya hanya membuat satu wawancara pendek dengannya 2019, dan masih banyak pandanganya yang belum lagi saya kongsikan:

Pada hari-hari sebelum Internet, ketika kita bergantung pada media cetak, radio, dan TV, sebenarnya, ada penyaring maklumat. Ada orang di sebalik rancangan TV, rancangan radio, penyunting surat khabar - mereka memutuskan apa yang ditunjukkan, jadi terdapat fungsi ‘penjaga pintu’ yang memastikan pandangan tanpa tauliah, pandangan yang tidak berasas, dijauhkan dari wacana umum kerana persoalannya, siapakah mereka dan kenapa mereka berkata demikian?

Tetapi dengan rangkaian sosial, tidak kiralah siapa kita. Kita boleh meletakkan apa-apa sahaja dalam Internet dan jika ia menjadi tular, maka tidak ada yang peduli siapa di sebaliknya. Kita hanya berminat dengan kandungannya. Oleh itu, ketanpanamaan tidak memberi perbezaan kepada “kualiti” atau tahap minat dalam hantaran itu. Berita menjadi apa-apa sahaja yang diminati, apa-apa yang ingin dikongsikan. Kita tidak perlu peduli tentang siapa yang menghasilkan kandungannya.

Dalam talian, kandungan yang dihasilkan pengguna tidak mempunyai sebarang penyaring maklumat - atau penyunting. Penyunting, secara tradisional, memutuskan sama ada sesuatu diterbitkan atau tidak. Mereka memastikan kredibiliti dan kualiti kandungan. Mereka juga memutuskan urutan kepentingan setiap berita. Ia tidak ditentukan oleh populariti atau keuntungan.

Tetapi untuk jaringan media sosial, keterlihatan cerita ditetapkan oleh populariti dan keuntungan. Mereka menjadi penyunting berita tanpa benar-benar memikul tanggungjawab penyuntingan. Dan sekiranya kita berpendapat bahawa ianya mustahil untuk mengawal (moderate) kandungan, maka pertimbangkan ini: Mengapa ianya sangat sukar untuk mencari kandungan lucah di Facebook atau Instagram?