The 225th Block: Fact check v Reality check

Well, actually...

This week…

Your reading time is about 15 minutes. Let’s start.

I am writing about fact-checking, but I will start with Minnesota governor Tim Walz’s boo-boos. I come from a media analysis perspective, so even if you’re not here for US-centric stories, I want to assure you that this applies to any journalism beat anywhere in the world—not just US politics. But if that’s also not your jam and you’re just here for The Hyperlinks, skip to the next part!

Here’s the back story by Chris Megerian and Laura Ungar for AP:

In March, after an Alabama court halted in vitro fertilisation procedures in the state, Minnesota governor Tim Walz decided to speak about his struggle to have children with his wife, Gwen. The same month, his team sent a fundraising email titled “our IVF journey” sharing an article that referenced “his family’s IVF journey” in the headline.

And earlier this month, Walz criticised Ohio senator JD Vance, the Republican candidate for vice president, by saying, “If it was up to him, I wouldn’t have a family because of IVF.”

In introducing himself to voters as Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris’ running mate, Walz has made his family’s struggle with fertility a central part of his narrative, a tangible way to connect with voters alarmed at the erosion of reproductive rights in the U.S. But Gwen Walz on Tuesday issued a statement that detailed the experience more comprehensively and disclosed that they relied on a different process known as intrauterine insemination, or IUI.

IVF v. IUI

IUI is usually done before IVF because it is more straightforward and therefore less expensive. You collect sperm, usually washed from the seminal fluid to increase success, and put it in the uterus and hope fertilisation happens. If IUI does not yield the expected result after one or several attempts, IVF is usually the next step.

With IVF, you have to stimulate the ovaries to help make a lot of eggs—instead of the usual one or two per cycle—get them to mature, retrieve them, and fertilise them in a dish with the prepared sperm, which sometimes need to be carefully selected by the embryologist because not all sperm are doing alright. Then you pick the best-performing embryo (fertilised egg) from the little dish, transfer it into the uterus and hope it results in a pregnancy. You also sometimes freeze the other embryos from this batch in case this particular embryo doesn’t stick, because to have to go through the egg preparation and retrieval again is pretty brutal. But sometimes the IVF works and now you have a few spare embryos in the fridge that you don’t need. And because storage is not free, you might decide to discard them.

Unlike IVF, IUI does not involve producing unused embryos, which anti-abortionists believe are unborn children. That’s why IVF is controversial in the US, but IUI is, for now, not under attack.

Context clues, anyone?

Because Walz claimed to have undergone IVF, when in fact it was IUI, Vance branded him a liar. Fact-checkers, both professional and amateur, went rabid. But I think people need to remember to understand context clues. IVF is the catch-all term for assisted reproductive technology, like Kleenex is for any facial tissue. Unless you are a reproductive health care provider, or someone who has been through fertility treatments, or planning to undergo one, you’re more than likely not to have heard of IUI or know how it’s different from IVF, and, for the most part, that’s okay.

Before I continue, let me be clear: I empathise with and understand the mandate of professional fact-checkers, whose role rose to prominence because of the lack of it when lies were spewed relentlessly in the advent of the “fake news” era. However, forcing a false balance in fact-checking efforts—a variant of bothsidesism—to appear impartial is performative and a disservice to journalism. The fact-checking industrial complex is pretentiously pedantic because the media outlets carrying out these efforts are trying very hard—not just to hold powerful people accountable—but to seize every opportunity to demonstrate that they are unbiased and treat everyone the same. A service to self, not to the people.

I concede that Walz probably warrants extra scrutiny; this was not the first time he had been inaccurate. An earlier version of his official campaign website stated that he retired as a command sergeant major of the US Army National Guard. This is partially true because he was promoted to command sergeant major and served as one until his retirement. However, he retired before he completed his academic training to remain a command sergeant major, so he retired with the retirement benefits and the rank of master sergeant, which is a pay grade below it. Additionally, in 2018, Walz also spoke about “weapons of war that [he] carried,” while never having served in combat, which Vance brought up recently to accuse him of stolen valour and prompted the Harris campaign to respond that he “misspoke.”

Hello, Sheldon Cooper!

Dear readers, are we all neurodivergent? Why are we taking every phrasing in the literal sense?? I mean, does Walz need to be more careful when telling all his dad-coded stories? Probably! But did he have any malicious intent? Probably not! Intent is extremely hard to prove though, even in a court of law.

Funnily enough, a letter signed by Republicans in Congress attacking Walz’s fitness for office because of his misstatements about his military service showed the same loose language used. While all signatories served in the military, VoteVets, a political action committee of veterans, tweeted that more than half signed as retired service members when they did not serve long enough to qualify for that designation. In the US, you need 20 years of service or medical exceptions to formally retire. Otherwise, you should, technically be known as a former service member.

“If you’re going to make a huge stink over semantics in reference to military service, then you better damned well get everything exactly correct when you do so,” said Jon Soltz, the chair of VoteVets told NYT ($). “Normally, we wouldn’t even raise a fuss over any of this, but if they want to play this game, then game on.”

Some misinformation—and deliberate, deceitful disinformation—is obvious. But misleading connections, inaccurate but everyday language, or out-of-context material? That’s tricky. That’s the reason fact-checking conclusions rarely are conclusively “true” or “false” but rather, “partially” or “mostly” true or false. And it begs the question, is it worth it? It is surrendering to a self-inflicted aberration of firehosing, walking right into the trappings of disinformation operations, where the misplaced energy could have been spent elsewhere more worthwhile. Journalism is already a haemorrhaging industry, for goodness’ sake!

As I write this, I am constantly checking myself for implicit bias because I wonder if I would afford the same leniency if it were Vance in Walz’s spot. Would I consider it petty? Ruthless? A double standard? I don’t know! But I know I am not the first to critically examine fact-checking (as Jon Allsop pointed out in his CJR piece, in 2019 Ana Marie Cox argued that “the exercise was overly bogged down in petty minutiae, and thus often missed the bigger picture”) nor is this the first time I am challenged to address it.

The trouble with looking for trouble

During my press fellowship in 2019 at the University of Cambridge, I met the then-head of the science department at Swedish public radio Sveriges Radio, Ulrika Björkstén. Among the views she shared with me is how tiring and counterproductive fact-checking can be, especially where science journalism is concerned. I would direct you to the podcast version of this but I fear it is a bit dated, and I am also embarrassed by my response to her position, which was essentially, “Yeah, okay, so we need fact-checking as a separate and independent vocation, not something that journalists do, got it.” You know, like how barbers used to carry out surgeries but now surgeries are conducted by surgeons, whose profession is completely unrelated to and distinct from barbering.

I now realise that that is too simplistic and probably why we got to where we are now. But here’s the gist: More often than not, scientific research isn’t straightforward. Scientific discoveries often don’t come by way of one-off studies, but are the result of a long, slow process of repeated tests, scrutinised through peer-to-peer reviews, going through multiple trials—and errors. Single studies do contradict one another. Yet these studies are often reported too eagerly, without a critical lens, and without awaiting scientific consensus.

The communication departments of universities bear some responsibilities too, sometimes packaging these scientific stories in an appealing and removing all uncertainties to attract media attention. This is a tangent, but only slightly. William Hitchcock, a historian at the University of Virginia, wrote on Threads, “One thing newspapers and universities have in common now is a delusion that bothsidesism is intellectually appealing, honest, or somehow ‘grownup.’ In fact, it’s a cowardly way to avoid having a moral or ethical position on anything, and it is a symptom of necrosis in public discourse.”

In an unrelated case, Björkstén shared how in Sweden, there was a political discussion about whether the country should have a special tax for the aviation industry, which would cost less, or whether they should be made to switch to biofuels. The Green Party, which is more left-leaning, wanted the tax, whereas the Liberal Greens said it would have a higher effect on carbon emission reduction if biofuels were introduced.

There was a rush to fact-check what the politicians were saying and numbers were run to find out which was more expensive, and which had more impact. But the reality was that while you would see a big impact on climate action if the money was spent on biofuels rather than taxation, the problem—later realised—was that there was no way to deliver that much biofuel. Mathematically, there wasn’t enough land mass, and the production rate wouldn’t meet the actual demand. It was simply not a realistic proposition based on currently available technology. It did not matter whether the Liberal Greens’ claims were true or false if the truth was not doable.

So, while sympathetic to the reality that people long for and deserve clear and accurate messaging, Björkstén was unhappy with this dogmatic movement of needing immediate, indisputable, cold, hard, fact-checking because it “kind of plays into an authoritarian rhetoric,” which could backfire.

How? Let’s consider this: If people start looking into the history of the most commonplace treatments millions of people receive everywhere every day, they will realise that along the way there were multiple failed clinical trials, wrong hypotheses, and other bioethical quandaries before we arrive where we are. HeLa, for one, is a famous example. Such “cold, hard, fact-checking” of medicine, of its long record of debunked theories, false premises, and questionable practices, could turn many away from the evidence-based health care that it is today because we have normalised uncompromising, overzealous, and absolute truths. It’s not the gotcha you think it is.

WeLL, aCtuALLy…

Naomi Lachance wrote that fact-check columns have been in desperate want of critical thinking. In a Rolling Stone article that analysed the US media’s fact-checking response to the 2024 Democratic National Convention that took place this week, Lanchance provided several examples, including:

At the New York Times, a baffling fact check on President Joe Biden lacked some basic arithmetic. They quoted Biden on Donald Trump: “He created the largest debt any president had in four years with his two trillion dollars tax cut for the wealthy.”

The Times decided this is “misleading.” They wrote that Trump’s administration “did rack up more debt than any other in raw dollars—about $7.9 trillion.” However, they wrote: “But the debt rose more under President Barack Obama’s eight years than under Mr. Trump’s four years.” So in other words, Biden was right, and eight is greater than four.

Ironically, the Washington Post issued a fact check at the top of their own Tuesday fact check. They incorrectly said that the contents of Trump’s letters to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un were unknown. In reality, they now acknowledge, parts of the letters were published by their own associate editor Bob Woodward.

When they initially considered former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s claim that Harris “won’t be sending love letters to dictators,” they wrote: “There is no evidence that Trump sent such letters. Clinton is making a bit of a leap to suggest that Trump has written ‘love letters’ to dictators.” Now, they have cautiously changed their stance: “This is in the eye of the beholder.”

The mental gymnastics?? As the ex-editor at Chicago Tribune and Sun-Times Mark Jacobs posted on Threads, “It took a fire to show us that the fire alarm was broken.”

Remember, not everything is fact-checkable. So maybe, instead of constantly arriving at inconclusive fact-checking verdicts, making us merchants of doubt who plant the seeds of suspicion and conspiratorial beliefs (and for what good, exactly?), we should consider shifting our attention to the context and the bigger picture instead.

And now, a selection of top stories on my radar, a few personal recommendations, and the chart of the week.

ICYMI: The Previous Block was mostly bad news, sorry. FWIW:

Is legal jargon actually a ‘magic spell’? Science says maybe by Francis Mollica (The University of Melbourne) for The Conversation.

The citation black market by Dalmeet Singh Chawla for Nature.

X says it is closing operations in Brazil due to judge’s content orders by Luana Maria Benedito for Reuters.

CORRECTION NOTICE: None notified.NEW MEDIA

Indigenous creators are clashing with YouTube’s and Instagram’s sensitive content bans

Gabriel Daros for Rest of World:

Shortly after Diamantha Aweti Kalapalo posted a video of a funeral ceremony in her village on YouTube in 2016, the platform took it down for violating its policy on child safety, which includes the prohibition of sexually explicit content.

In the video, a couple of tribesmen marched across a dirt road in Xingu, in the wild heartlands of central-west Brazil, playing long ceremonial flutes. Two raven-haired women trailed them, wearing their traditional outfit: a necklace and loincloth.

Such takedowns have become par for the course for Brazilian Indigenous content creators like Kalapalo who have taken to social media in recent years to increase awareness about their cultures and gain a kind of financial independence. Censorship from social media platforms has forced them to sanitise their content, eliciting concern among academics who believe that doing so erodes their archival records.

Loosely linked:

In hard times for media companies, these people are working to bolster Indigenous news coverage in Sask. by Ethan Williams for CBC.

Readers prefer to click on a clear, simple headline—like this one by David Markowitz (Michigan State University), Hillary Shulman (The Ohio State University), and Todd Rogers (Harvard Kennedy School) for The Conversation.

Internet goes wild for Chinese video game even as reviewers bash censorship by Mithil Aggarwal for NBC.

Actors demand action over ‘disgusting’ explicit video game scenes by Chris Vallance for BBC.

ETHICS & PROPAGANDA

Canada’s Conservatives criticised over ‘Our Home’ video featuring scenes from US, UK, and Serbia

Leyland Cecco for The Guardian:

The video, titled “Canada. Our Home” was initially posted to X on Saturday, with various scenes overlaid by a speech from the party leader, Pierre Poilievre. The Conservatives, who lead the governing Liberals in the polls, are preparing for what is widely expected to be a bitterly contested federal election.

Soon after the video was posted online, viewers pointed out much of the footage depicted as “Canadian” was easily traced to places outside the country. A thread on X by the Calgary-based user @disorderedyyc compiled at least 13 inconsistencies, adding: “If you’re making a video about the Canada ‘we know and love’, you should be using actual Canadian footage.”

Among the gaffes: a “Canadian dad” driving through the suburbs was actually stock footage from North Dakota in the United States, a clip of children attending class was shot in Serbia, the “Canadian-built” homes were under construction in Slovenia, and a university student “late for class” was filmed at a post-secondary institution in Ukraine.

The original video was deleted, but the Internet never forgets. You can always count on someone to archive it. Loosely linked:

Conservative network to bring US far-right provocateur Chris Rufo to Alberta by John Woodside for CNO. Anti-science nurse Anne Jordan is one of the speakers. The event is sponsored by, among others, Mastercard, Meta, The Coca-Cola Company, Doordash, and Sun Life.

India’s alternative facts: how the government of Narendra Modi invents its own kind of ‘experts’ to legitimise its policies by Anuradha Sajjanhar (University of East Anglia) for The Conversation.

A war on universities in the Netherlands by Tim Brinkhof for New Lines Magazine.

Sextortion guides and manuals found on Telegram and Youtube by Libby Brooks for The Guardian.

Telegram messaging app CEO Pavel Durov arrested in France by Ingrid Melander and Guy Faulconbridge for Reuters.

AI & ALGORITHM

The SEA-LION can roar

Cha Hae Won for Fulcrum:

Trained on content produced in Southeast Asian languages like Bahasa Indonesia, Thai and Vietnamese, SEA-LION distinguishes itself from other LLMs, which are trained primarily on the corpus of English Internet content. By employing SEABPETokenizer, a form of tokenisation specifically tailored for Southeast Asian languages, SEA-LION is highly adept at understanding Southeast Asian languages and capturing local cultural nuances.

In a demonstration shown to the author by AI Singapore, SEA-LION, Meta’s Llama 2, OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Alibaba’s SEA-LLM were given a prompt that enquired about the benefits of ojek . In Indonesia, an ojek refers to a motorcycle taxi, and comes not only in the form of traditional street-hailing but also the modern online form pioneered by Gojek. SEA-LION accurately responded to the prompt by highlighting the role of ojek in providing faster transportation. In contrast, Meta’s Llama 2 and Alibaba’s SEA-LLM primarily focused on Gojek and excluded references to the traditional offline taxis that are still in operation.

In another assessment, LLMs were given a prompt in Thai to describe ASEAN in Bahasa Indonesia. SEA-LION was able to give an accurate output in the right language. Contrastingly, Llama 2 failed to understand the Thai prompt. SEA-LLM answered in Thai instead of Bahasa Indonesia and even “hallucinated,” saying that ASEAN is comprised of 11 member nations, including countries such as Venezuela.

Loosely linked:

The unstoppable rise of Chubby: Why TikTok’s AI-generated cat could be the future of the Internet by Aidan Walker for BBC.

A new ‘AI scientist’ can write science papers without any human input. Here’s why that’s a problem by Karin Verspoor (RMIT University) for The Conversation.

AI pioneers want bots to replace human teachers—here’s why that’s unlikely by Annette Vee (University of Pittsburgh) for The Conversation.

Hard-pressed Kenyan drivers defy Uber’s algorithm, set their own fares by Edwin Okoth for Reuters.

Other curious links, including en español et français

LONG READ | The rise of ransomware gangs by Caitlin Walsh Miller for Maclean’s.

Readers trust journalists less when they debunk rather than confirm claims by Randy Stein (California State Polytechnic University) and Caroline Meyersohn (California State Polytechnic University) for The Conversation.

A un año del “Se acabó” por Irene Zugasti en CTXT.

El rol de género en el arte contemporáneo: más allá de las modas y la discriminación por Agustín Millán en Diario16+.

“Especulamos para sobrevivir”: cómo el ultraliberalismo y la precariedad crearon a los ‘criptobros’ por Enrique Rey en El País.

La démocratie québécoise sous l’influence des réseaux sociaux par Thomas Laberge dans La Presse Canadienne / Le Devoir.

Faut-il se méfier de Monica, le site qui utilise l'intelligence artificielle pour se moquer de ses utilisateurs ? par Luc Chagnon dans Franceinfo.

Avant la rentrée, des élèves arnaqués sur Internet se font soutirer leurs informations personnelles par Iris Shimizu dans Libé.

What I read, listen, and watch

I’m reading Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational (2022) by Michael Shermer. I think we’re not rational beings, we’re rationalising beings. Nonetheless, great analyses of conspiratorial beliefs and the role of psychology, politics, media, and education in the “marketplace of ideas.”

I’m listening to Click Here to learn why Unit 221B’s Alison Nixon finds young cybercriminals “objectively interesting.”

I’m watching ABC’s Foreign Correspondent episode on badly behaving monks (to put it mildly) in Thailand.

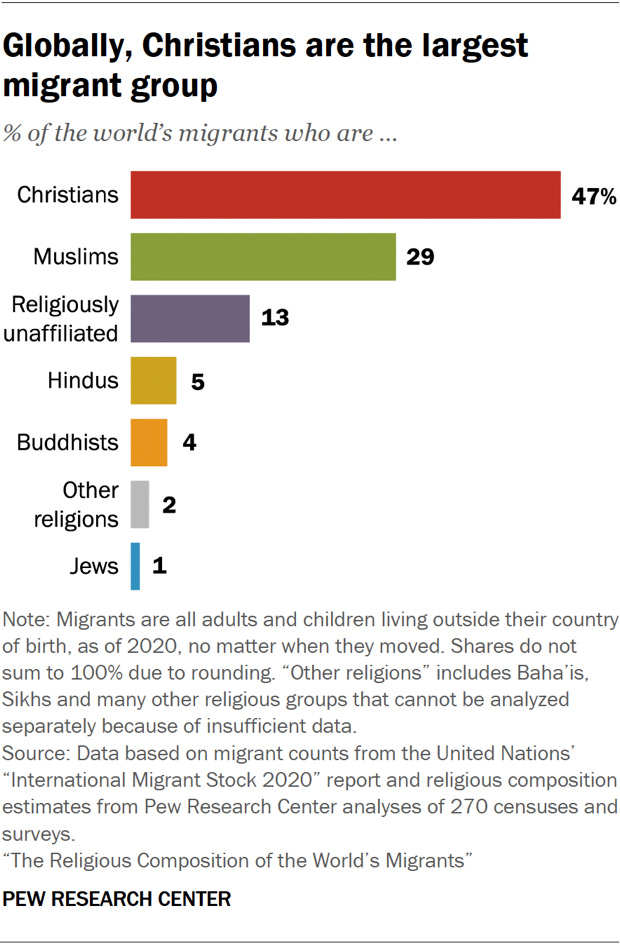

Chart of the week

Hey, did you know that globally, Christians are the largest migrant group? Here is Stephanie Kramer and Yunping Tong’s report on the religious composition of the world's migrants for Pew Research Center.