The Extra Mile: Fact-Checking & Privacy Checkup

A master post to living a smarter and safer digital life.

In this master post, you will find:

A checklist for fact-checking before sharing:

Credentials: Who published it and are they reputable? This is why all the links I share have the names of the publisher and author.

Publishers should have an About Us section.

Journalists should have a bio with their specialisation and/or background.

Check the language used in these sections for biases.

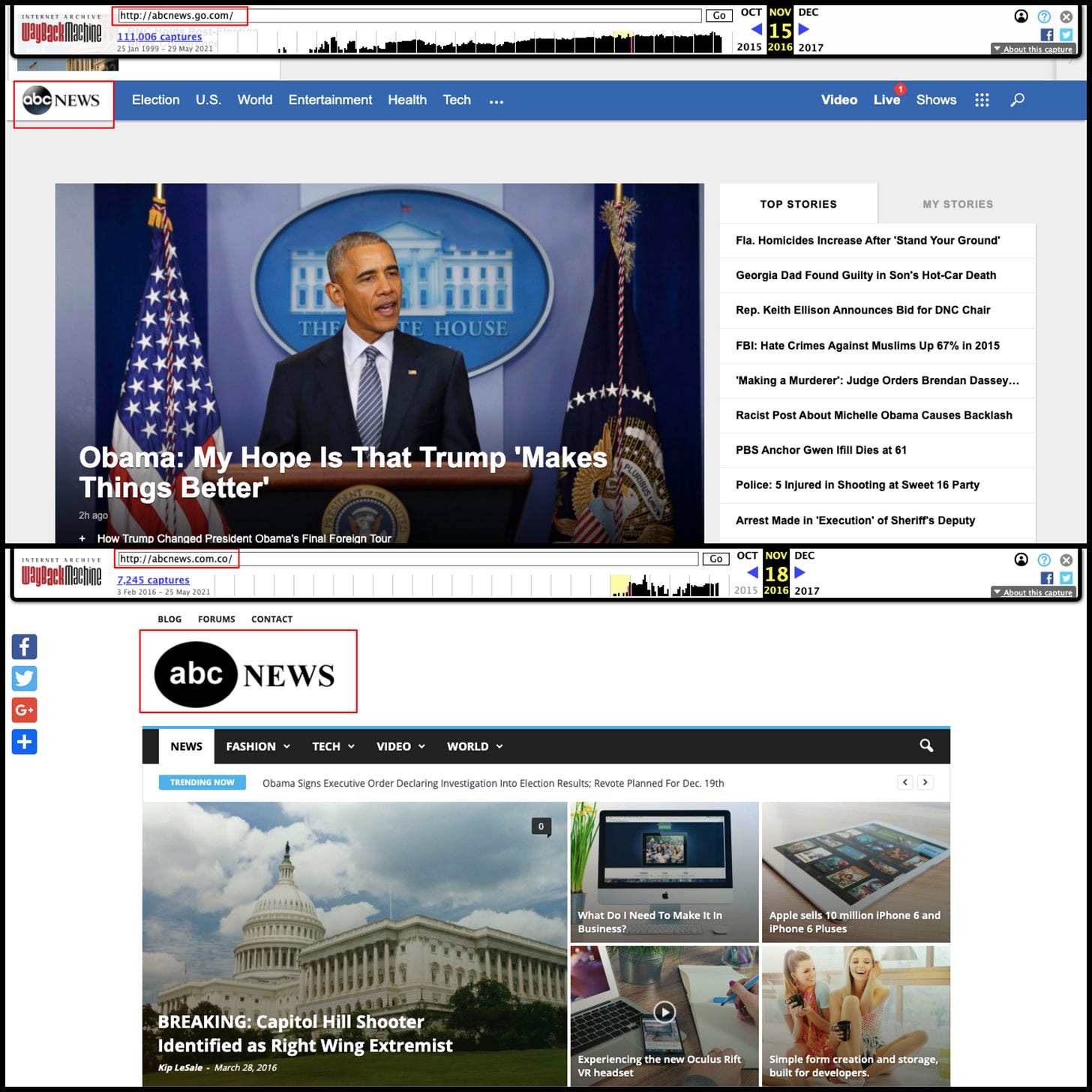

Check URLs and logos. The greatest pretenders mimic authentic publications almost to a tee. Avoid AMP, which masks the original URLs1 especially when viewing sites on mobile browsers.

Date: When was it published? The Guardian improved the way its old stories are labelled so you can see a yellow banner2 that tells you the age of the story before you even click the link.

If it’s not current, is it relevant to read and share now?

If it’s relevant, what is the purpose of reading and resharing?

Sources: Does it cite reliable sources and does it link to the primary (original) source, such as a peer-reviewed paper? [Note: More on this in the next sections.]

Does the primary source disclose conflict of interest?

If it’s a piece of research: Are the datasets made publicly available? Are the methodologies rigorous? Do others, especially experts in the same field, quote or cite this source?

If it is a first-hand witness of an event: Can this person provide evidence? Did the journalist verify this information, for example, is the media file manipulated, staged or taken out of context?

People and Places: Is anyone else reporting it and who are their audiences?

If not, why?

If yes, are they wording the same story differently?

Who is sharing it and where are they sharing it?

Who is behind those accounts and what are their affiliations?

A step-by-step guide to skimming journal articles:

Install Unpaywall, a free browser extension that crawls the internet to find full-text papers from legal sources.

Do a quick search on the name of the journal. Some papers are published in predatory ‘journals’ or without peer review. A DOI3 does not automatically make an online journal reputable.

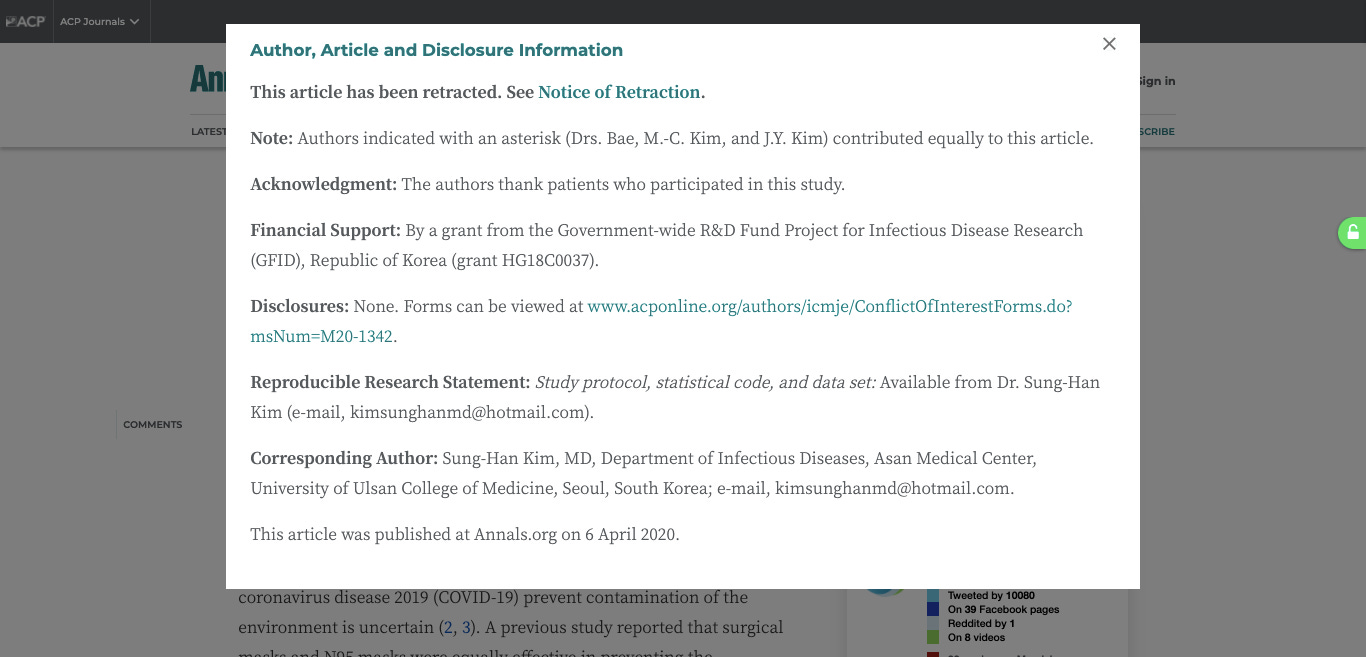

Check for retractions and corrections: Usually if a paper is retracted or if there is a correction made, a bright text box at the top of the page will notify you.

Check the publication date. If it’s a paper published before you were born, it may be outdated, but not always.

Most online journals have a citation list that shows a list of other studies that have quoted this paper. What other similar studies have been done?

You can click on the citation list to find out what are the latest studies in the field. You will repeat this process from the top for each study.

Cross-check authors and their affiliations. Do they exist and are they who they say they are? Note: If the study is qualitative, is the research team diverse to prevent narrowed and/or skewed findings?

Read the disclosure information. Here, it will give you a notice of any conflict of interest, such as if the study was funded by an interest group or if an author is affiliated with an interest group. You will adjust your scepticism based on the statement(s).

Then, we start to read the introduction, not the abstract. This segment is where you will the Big Question that the researchers want to find the answer to through their study. Reading the abstract is like reading news headlines, it may give you some context but the devil is in the detail.

Then, go to the study design and methodology. Depending on the type of research done, it might get very technical, but there are certain things to look out for. For instance:

Sample size: If the study involves 10,000 people, it’s probably more representative of the general population. If it’s 10 people, you can probably close the tab.

Data collection method: Is the information gathered based on the researcher’s observation of the test subjects, or is it self-reported by the test subjects? You can be more sceptical if it is only self-reported.

Then, you can also go to the study limitations. This is often towards the end of the discussion section of the paper. Here, the authors will outline the limitations of the study design. For example:

They might say that they do not know the effects of their study “outside of a clinically controlled setting.”

Some studies are designed in such an artificial environment that they “cannot possibly represent what really happens in the real world.”

Here, you can again adjust your level of scepticism based on the limitations of the study.

Once you have completed these steps, you can now read the paper in full, including the findings, which are in the results, discussion and/or conclusion sections.

First, what are the results?

Second, what do the results mean?

You will find words such as ‘confidence intervals’ and ‘statistically significant’ or ‘non-significant’.

You will find graphs with good or bad axes, with or without error bars.

Some statistical analyses can be quite daunting or seem meaningless. If it’s something that you don’t understand and it’s preventing you from following the study, don’t worry about it.

The more you practise, the better you’ll get. You don’t have to be a professional football player to know a good kick from a bad one; you just need to watch enough football.

Some journals have a comment section where academic commenters too seek clarification and it is usually not written in academese. A good comment section will show the commenter’s full name and affiliation so that you can decide on their credibility.

Then, the second to last step is to go back to the introduction: Did the researchers answer the Big Question?

And finally, read the abstract: Does it represent the study and its findings or does it show a biased interpretation by the authors? Adjust your scepticism one last time.

Fact-checking, verification — open-source tools

Fact-checking and verification are often used interchangeably even though they mean different things. Furthermore, traditional pre-publication fact-checking (also known as editing) — such as the ones carried out by magazines to confirm dates and locations or to attribute the right quotes to the right people before going to print — should not be confused with ex-post (after-the-fact) fact-checking.

Verification

What: Verification is a newsgathering technique to ensure something is factual.

Who: It is usually used to examine user-generated content (UGC).

When: It is used before the UGC gets published.

Why: If found to be false, it should not be published — or published to describe its falsehood explicitly.

How: Trace primary source, conduct background checks, interview witnesses of the event and producers of UGC, examine UGC with various tools such as the ones compiled by First Draft4. While there are many, here are the tools I have actually used consistently:

Image verification: Google Image, TinEye (reverse image search), Jeffrey’s Image Metadata Viewer, VerExif, Sensity (for deepfake detection)

Video verification: InVID/WeVerify, Watch Frame by Frame, Amnesty International’s Youtube Data Viewer

Maps, geolocation and crowd size: Google Earth/Maps, MapChecking (crowd size estimator), LatLong (reverse geocoding lat long to address)

Time and place: Time Zone Converter, Wolfram Alpha (for weather on any day), SunCalc (determine the time of the day an image is taken), Epoch & Unix Timestamp Converter

Plagiarism check: Grammarly (English only), Plagiarism Checker, CopyLeaks (for website comparison, compatible with most languages)

Social media trends: CrowdTangle, Google Alerts, Google Trends

People: Webmii, Social Searcher, LinkedIn

Domains: IP Lookup, ICANN Lookup, Wayback Machine

Fact-checking

What: Fact-checking is used for statements related to the public interest.

Who: It is used especially when a statement is issued by politicians or academics.

When: The fact-checking process is made during or after the release of a statement, as it is usually made during a press conference, a live interview, or published on the social media platforms of the newsmaker.

Why: Most of these statements are made in a live setting, such as in a press conference or TV interview, or published on the social media platforms of the newsmaker. The claims need to be checked, corrected (if false) or contextualised as they are being made or soon after.

How: Cross-check the statement with other sources such as relevant and reliable official statistics and consult with top authorities and/or high-quality secondary experts to determine its veracity and correctness. Here is how to vet them:

Basic online search: ResearchGate, Academia, Google Scholar

Who founded, fund and run their organisation(s)?

What industries or otherwise, interests, do they represent?

Are their organisation(s) non-profit and non-partisan?

What are their credentials?

Can the accreditation bodies confirm these certifications were issued?

Do they have credentials that are revoked or otherwise expired? If so, why?

Do other relevant experts cite and quote this expert in their works? Otherwise, do they have a track record that can be evaluated?

Have they examined the subject matter in question? Eg. Reading the published transcript of the claims, or going through the complete data set of a survey that they are asked to analyse.

Are they able to demonstrate how they arrive at their conclusions in a transparent manner?

Take the test

Not all claims are fact-checkable. Here are some examples from the Hands-On Fact-Checking5 course (which you can take for free) by the International Fact-Checking Network at Poynter Institute & American Press Institute:

“The unemployment rate has decreased by two points in the four months since I became President.” Answer: It is verifiable through a national statistical agency.

“The private sector’s confidence in my government has led to a 2-point decrease in the unemployment figures.” Answer: The statement injects a claim of causation, but the correlation is not causation.

“Without my government, we wouldn’t have seen unemployment fall by two points.” Answer: The claim is an opinion but there is no way to know what would have happened to the unemployment rate had the country been governed by someone else. The claim is not supported in facts.

Sensible tools and tips for digital privacy

These tools and tips are for the general population but with some considerations for those doing low to medium-low risk journalism and activism, and similar activities. All the recommended services here are free, or they have a free version—but as the saying goes, privacy is not a product, it’s a process.6 7 8

These tools and tips apply to ALL devices with a computer or cellular network, wired or wireless. That means everything from your desktop computer to your smartwatches that are connected to Wi-Fi, 5G, Bluetooth, cable Internet, and others.

Device Setting

Turn off home screen notification so that nothing can be shown without first unlocking devices.

Make it fast and easy to lock device screen—with a click of a button, preferably.

Enable instant access to the device camera from the locked home screen.

Make it possible to remotely lock, reset, and/or securely erase data from devices.

When not in use, turn off location, turn on aeroplane mode, turn off Airdrop.

When not in use, cover your camera, including the front-facing phone camera, as well. Otherwise, at least hover a finger over it when browsing ad-driven platforms, especially Instagram.

Anti-malware: Open-source is usually preferable.

Be mindful of who’s around you, and what they’re doing, especially in locations that you frequent, such as your own neighbourhood and workplace building. Having your face in the background of your neighbour’s backyard barbecue live stream is all it takes to know your home address.

Media Management

Consider a one-tap access to a voice recorder app for instant audio notetaking.

Delete all metadata such as date and time, GPS location, device type from any media—images, videos, audio files, even Word documents—before posting.

Blur or block faces, and other easily identifiable markers eg. city landmarks, in captured media before posting anywhere. Take note: In some jurisdictions, it is illegal to record someone without consent.

Live video footage: Be wary of what is streamed, including what and who is in the background. This includes video calls, virtual meetings and live streams in private and in public.

Screenshots and screen-sharing: Keep desktop clear of files; use empty desktop if possible. Use incognito browser mode, disable the bookmark bar, and close all tabs before capturing or screen-sharing your browser.

Instead of iCloud or Dropbox, consider using encrypted privacy-focused synch services such as Nextcloud to store and sync files across multiple devices.

To capture, store and access sensitive files: Use air-gapped devices. Instead of a smart device, use an old school audio recorder or camera. Store and access sensitive media in an air-gapped device, such as a hard drive, encrypted if possible, easily destroyed if necessary.

Consider using pen and paper, which has more legal rights to privacy than digital devices, to take and store notes.

Web Browsing

Search engine: Instead of Google, try DuckDuckGo.

Block ads and third-party trackers with browser add-ons such as uBlock.

Use ClearURLs to remove tracking elements from URLs.

Use URL Redirect Checker even if the shortened URL doesn’t look shady.

Encrypt connections to most major websites with HTTPS Everywhere.

Use proxy or VPN such as ProtonVPN.

Check for IP address and DNS leak periodically.

Periodically delete cookies and browsing history.

Clean up your bookmarks and reading list periodically.

Periodically scrub old activities and/or turn off activity tracker on Google services such as Youtube and others that you cannot be off of.

Data scrambling and data masking: Periodically contribute useless or misleading data to confuse targetted ads services and algorithms. Use incognito browsing mode, pause search history, search for random things, and click on things that don’t interest you. Try AdNauseam to automate the process.

Browser fingerprinting: Ironically, every time you do something with your browser, such as installing privacy-protection extensions, you change your browser’s fingerprint, making it more unique, thus more identifiable. Find out how unique your browser is with EFF’s Panopticlick.

Avoiding browser fingerprinting: Start fresh with a new device, do not synch with the others. Create a new email account for that device. Use a different, maybe, public network. Use a basic, unmodified browser version to blend in.

Communication

It would make sense to have separate professional and personal phone numbers and email addresses that are kept independent from each other, ie. no synching. Use temporary emails to keep spam at bay.

Do not include details that can potentially confirm your personal and professional relationship with your contact list, eg. “❤️Mum❤️” or “Supervisor”.

Use encrypted messaging apps such as Signal.

Use secure email services such as ProtonMail.

End-to-end encryption for communication, always, but consider that in some countries encrypting your files is illegal.

Detect and block email trackers with services such as Trocker.

Account Management

If you have a vocation that is public in nature, eg. if you are an activist or a journalist, separate your private and public social media accounts, if needed.

Spring clean inboxes, and social media accounts—delete messages, emails, tweets, shared media, status updates, and others, periodically.

Periodically change very strong passwords or use a password manager or both.

Use two-factor verification, always.

Do not use auto form filler for personal details such as address and credit card.

If you forget your password and request for an email to reset, don’t just delete the email, delete emails forever.

Periodically check for data breaches using Have I Been Pwned.

Periodically search for your usernames, emails, and phone numbers for leaked information using Google. Change passwords or delete these accounts.

When using web services that require an email, consider using a burner account where the personal information cannot be easily linked back to you.

Manage third-party signups that use your Facebook or Google accounts by periodically reviewing and revoking access for services no longer used.

Delete inactive accounts linked to your email. Just Delete Me has a directory of web services that require user email. It tells you which ones use dark pattern techniques to make it difficult—or even impossible—to delete your account.

Delete inactive accounts linked to your username. You can use Namechk to find the list of web services if you have the same username across the board.

Ubl, M. (2018, January 9). Improving URLs for AMP pages. https://amphtml.wordpress.com/2018/01/09/improving-urls-for-amp-pages/amp/

Moran, C. (2019, April 2). Why we’re making the age of our journalism clearer at the Guardian. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/help/insideguardian/2019/apr/02/why-were-making-the-age-of-our-journalism-clearer

Davidson, L. A., & Douglas, K. (1998). Digital object identifiers: Promise and problems for scholarly publishing. The Journal of Electronic Publishing: JEP, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0004.203

First Draft - Basic Toolkit - start.me. (n.d.). Retrieved June 14, 2021, from https://start.me/p/vjv80b/first-draft-basic-toolkit

Hands-on Fact-checking: A Short Course - Poynter. (2018, September 5). https://www.poynter.org/shop/fact-checking/handson-factchecking/

Privacy Tools. (n.d.). Privacy Tools - Encryption Against Global Mass Surveillance. Privacy Tools. Retrieved June 16, 2021, from https://www.privacytools.io/

Tactical Technology Collective. (n.d.). Security in a Box – Digital-security tools & tactics. Security in a Box. Retrieved June 16, 2021, from https://securityinabox.org/en/

CrimethInc. Ex-Workers Collective. (n.d.). Doxcare. Crimethink. Retrieved June 20, 2021, from https://crimethinc.com/2020/08/26/doxcare-prevention-and-aftercare-for-those-targeted-by-doxxing-and-political-harassment

Really useful, thanks for this!

Bookmarked !