In Google we (dis)trust

Ashley Gold and Margaret Harding McGill for Axios: DC’s assault on tech will crest at CEO hearing. Big Tech CEOs testify before US House subcommittee on Monday; lawmakers will grill them on antitrust and market dominance, misinformation and content moderation, China, and data privacy.

Jeffrey A Trachtenberg for Wall Street Journal: WSJ journalists ask publisher for clearer distinction between news and opinion content. “The letter cites several examples of concern, including a recent essay by Vice President Mike Pence about coronavirus infections. The letter’s authors said [it was published] ‘without checking government figures’ and noted that the piece […] was later corrected.”

Nicholson Baker for Columbia Journalism Review: Youtube’s psychic wounds. “Seeking political news, Nicholson Baker ventures to the wrong clip and back again.” “This endless, crowd-curated theatre of ourselves, serves up the raw, the cooked, the failing, the helpful, and the WTF? any time you want it.”

Statistically speaking…

Because this week’s essay is much longer than usual, I have to redirect you to a separate post, and I hope you will find it insightful as I share about:

how data and statistics are interpreted and reported

basic fractions and unintentionally diluting homemade hand sanitisers

the importance of proportional representation

why some things are not to scale

why COVID-19 studies get published rapidly, and some retracted just as quickly

What I read, watch and listen to…

I’m reading the Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence position paper.

Otherwise, I’m reading BBC Mews. Because the Internet is made of cats.

I’m watching Broey Deschanel’s analysis of, in her words, “everyone's favourite smol bean, and his flaws,” Wes Anderson:

Chart of the week

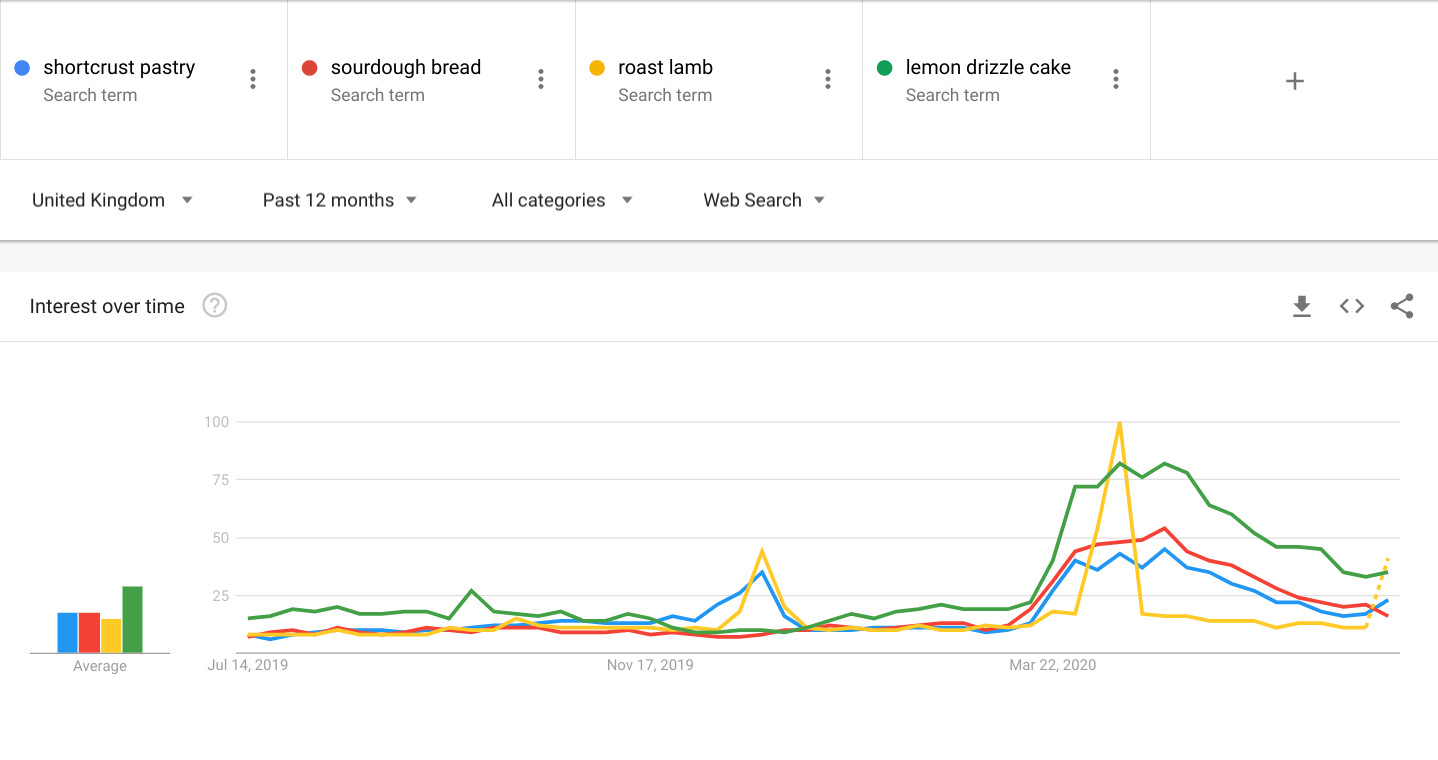

Head of Client Solutions and Analytics of Google UK Biren Kalaria wrote The story of UK lockdown through Google Trends. An interesting set of stats showing how people feel (“lower back pain”), what people know (“the quietest time to go shopping”), how people make a living (“what does furlough mean”), how people learn (“interior angles of a pentagon”), and what people do (“espresso martini”).

Orang muda dan Bahasa Melayu dalam media sosial – sebuah rumusan

Menurut Prof Dato’ Dr Teo Kok Seong dalam Wacana Ilmu bertajuk Orang Muda dan Bahasa Melayu dalam Media Sosial, siaran dalam media sosial “ yang ditulis dalam bahasa Melayu telah banyak mengubah sifat bahasa Melayu itu sendiri,” dan pelbagai gelaran diberikan bahasa Melayu dalam media sosial ini termasuklah:

bahasa Melayu semu – berbentuk seakan-akan bahasa Melayu, tetapi bukan bahasa Melayu yang sebenar

bahasa Melayu baharu – kerana bahasa Melayu yang digunakan dalam media sosial memiliki ciri-ciri baharu

suatu kelainan bahasa Melayu – seperti dialek bahasa Melayu yang lain

Asasnya, penggunaan bahasa Melayu dalam media sosial mempunyai ciri-ciri berbentuk jelek, seperti:

Tidak ada usaha penyuntingan, penyemakan dan pemantauan untuk memastikan ia mengikuti dan mematuhi amalan berbahasa yang lazim. Contoh ketara adalah penggunaan trengkas (shorthand), iaitu penggunaan singkatan seperti pu3 yang bermaksud puteri, iaitu 3 itu dibaca dalam bahasa Inggeris.

Satu faktor penting adalah persadanya, yang mempengaruhi penggunaan bahasa. Sebagai contoh, Twitter menghadkan ruangan huruf teks, maka kecendurang menggunakan trengkas adalah lebih tinggi.

Kosa kata yang sedia ada diberi makna baru yang fahamannya terhad kepada pengguna media sosial sahaja, iaitu berbentuk slanga. Contohnya, ciap(an), yang makna asalnya merujuk kepada bunyi anak ayam, diberi makna lain untuk merujuk kepada apa-apa yang dikongsi di dalam Twitter.

Kosa kata itu menjadi jelek apabila dipinjam terus dari bahasa Inggeris tanpa ada terjemahan langsung. Contohnya, otw dan lol membentuk bahasa rojak yang tidak pernah menjadi serapan kepada bahasa Melayu.

Bahasa jelek ini “tertumpah” ke dalam cara berbahasa orang kebanyakan sama ada secara lisan atau tulisan. Jalan tengah yang dicadangkannya dalam permasalahan ini adalah untuk “mengambil kira lingkungan penggunaan sebagai landasan” dan “menggunakan laras yang betul berdasarkan ranahnya.” Tambahnya:

Kita perlu dan wajib menggunakan bahasa yang baik dan betul dalam ranah formal kerana ia adalah bidang rasmi yang serius, maka bahasa yang digunakan itu perlu berperaturan. Manakala dalam ranah yang tidak formal, atas dasar kebebasan linguistik, kita boleh menggunakan bahasa yang tidak formal ini, yakni yang tidak sangat mengikuti peraturan.