The 284th Block: Talking about talking

Just because you can, doesn't mean you should

This week…

Your reading time is about 9 minutes. Let’s start.

I’ve been meaning to write this for a while, but I wanted to wait for the noise to die down. As summer turns into autumn — and everyone has to ask, “Betty Who, who?” once again — I think the time is right to talk about talking. Podcasting, specifically.

I’ve lost count of how many times companies have announced that they’re going to “pivot to audio,” only to reverse course months later. Is Clubhouse even still a thing? And I think the moderation of audio-based content still hasn’t caught up to the moderation of other media — even as AI-driven social media moderation continues to deteriorate in quality. Audio remains a largely unmoderated medium.

Take Made It Out, a podcast hosted by Mal Glowenke, a newly out content creator who, with Mathilde Jourdan, launched Made It Out Media as a community for queer women. (If you’re newly out, I get that it’s exciting to talk about your newly discovered side of your identity, but please, chill out, take time to self-reflect and don’t make a fool out of yourself.)

One particularly poorly received episode released in August featured Betty Who — who has been in a straight relationship for more than a decade, longer than same-sex marriage has even been legal nationwide in the U.S. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. But she had the audacity, in this current political climate, to lament that it felt like “a crime” to be in a cis-het relationship. She also insinuated that Renee Rapp, an out lesbian in a long-term relationship with another woman, could “fall in love with a man” in ten years.

For some people, sexuality may indeed be fluid — but for others, it really isn’t. That statement wasn’t just insulting; it was dismissive, if not downright dangerous, for suggesting that a lesbian would eventually find “the right man.” (If that’s not clear enough, it perpetuates the same harmful narrative men have often used to threaten or “convert” lesbians. You would hardly hear this said to a man, regardless of his sexuality.)

There were other aspects of the interview — both about the guest and her husband — that just came across as icky. In essence, it highlighted white queer privilege and entitlement: the tendency to wield queerness as a primary oppression card while leveraging it against other minorities. But that’s not the main point here.

The real issue is that throughout the entire episode, Glowenke simply hummed and fawned. If you are a (podcast) host you have a responsibility to push back when guests say things that are wrong or harmful. There was no evidence of media training, journalistic awareness, or even basic research. Everyone thinks they’re Oprah — but they’re not. Actually, scratch that — they’re probably more like Oprah than they think: minimal fact-checking, little accountability, and a willingness to lend their platform to spreading harm while chasing clout and lining their pockets.

Not everyone has the instincts to spot nonsense or bad faith. But if you don’t have that skill as a host, hire someone who does. Otherwise, you’re not really a host or an interviewer — you’re just a microphone stand with no thoughts, let alone critical ones.

The podcast ecosystem is overflowing with people who think they’re great conversationalists, conversating about conversations that ultimately converse about nothing. And audiences enable this because the chatter is light enough not to distract them from whatever else they’re doing while listening. It’s a win-win for publicists too: their artists get a platform where they won’t be challenged, only flattered through cute little fluff pieces.

It’s no surprise that Taylor Swift chose to announce her latest album on a podcast rather than through a media outlet. More crucially, podcasts have become both an entertainment and news platform — and people trust it. The talk-show format creates a sense of intimacy and authenticity. Audio makes you feel like your host is speaking personally, even privately, to you (#41, 2021). That intimacy is powerful — but also dangerous — because misinformation thrives on emotional connection. That parasocial bond makes listeners view hosts as credible and trustworthy, even though nearly 70 percent of the 36,000 political podcasts analysed by the Brookings Institution contained at least one unverified or false claim (Jason Weismueller, University of Western Australia / The Conversation, 2025).

The 2010s were the golden age of audio journalism — full of immersive storytelling and long-form narrative podcasts (Eric Benson, Rolling Stone, 2025). But by 2024, conversational podcasts had taken over the medium (Nicholas Quah, Vulture, 2024). In August, Amazon also announced the end of Wondery, the studio known for its rich narrative formats.

That shift wasn’t accidental. Narrative podcasts take time, effort, and money to produce. Talk shows, on the other hand, are cheaper, faster, and require far less journalistic rigor or production work. Jeanine Wright, a former Wondery executive, now leads a new firm, Inception Point AI, which manages more than 5,000 AI-generated shows and floods the market with over 3,000 episodes a week. Each episode takes about an hour to make from start to finish — and costs just one dollar (Caitlin Huston, The Hollywood Reporter, 2025).

All this makes podcasting sound like the simplest medium in the world. But I’d argue it’s actually one of the toughest — precisely because of its limitations (#42, 2021). Audio strips everything down to the voice, the tone, and the trust between host and listener. You have to actually communicate, not just create. Content creators, especially in audio, need more than charm. They need media training, an ethics code, and a grounding in journalism and media literacy. Because whether you’re telling a story or leading a conversation, the microphone is still a form of responsibility — and good hosts know and remember that.

Your Wikipedia this week: Clanker

And now, a selection of top stories on my radar, a few personal recommendations, and the chart of the week.

ICYMI: The Previous Block was about democracy in the online marketplace, and AI translations.

CORRECTION NOTICE: None notified. MISINFORMATION

The fledgling UN tried to rein in mass-scale misinformation. The world turned its back and is now paying the price

Roland Burke for The Guardian:

Every age assumes the dislocations of its time are exceptional, but the present one seems particularly indifferent to earlier moments of technologically induced disequilibrium. Almost exactly a century ago, the League of Nations, precursor to the United Nations, devoted substantial energies to the international suppression of obscene publications, animated in part by the purported corruptive power of the motion picture. There was even an international ban on such “obscene” products, which Australia eventually signed.

Maligned as it was, the League rapidly grasped the potential of the first truly transnational media form: the radio. Hopeful proposals for both radio and film in the service of peace, education and international understanding soon developed. Australia dutifully signed up to the relevant League treaty.

But more impressive perhaps was the League’s comparative agility when the pitfalls of radio, rather than their promises, became apparent. As the shadow of Nazi ideology began to fall on Geneva in the 1930s, League intellectuals and jurists conferred over several years on the threat posed by what was termed at the time “false news”. League conferences on the subject affirmed that “the campaign against the spread of inaccurate news was one of the necessities of international life” and mapped out countermeasures.

Their deliberations exemplified the prescient futility that characterised so much of the organisation: by the point at which propaganda radio broadcasts were formally banned in 1936, fascist forces were contesting not merely the airwaves, but the ground, the seas and the air.

Loosely linked:

In the age of false information, we all need a good BS detector. Here’s how to sort facts from harmful fiction by Tony Haymet for The Guardian.

YouTube opens ‘second chance’ program to creators banned for misinformation by Jay Peters for The Verge.

Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds: Lessons on media literacy by Carl Holm for DW.

When power meets the wellness algorithm: Why we mistake virality for truth by Rachael Kent for Full Fact.

Can AI save us from misinformation? by Wilf Dinnick for Maclean’s.

GAGGED ON THE INTERNET

How anti-cybercrime laws are weaponised to repress journalism

Nalova Akua for CJR:

In May 2024, Daniel Ojukwu, a twenty-six-year-old reporter for the Foundation for Investigative Journalism, a Nigerian nonprofit, was grabbed off the streets of Lagos by armed police and bundled into a vehicle. For the next several days, he was held in a cell incommunicado—first in Lagos, and later in the federal capital, Abuja—without being told exactly what he’d been arrested for. “It was more of an abduction,” Ojukwu recalled recently, via WhatsApp. Finally, on the fourth day, the authorities informed him that he was being accused of breaching a 2015 law known as the Cybercrime Act. His violation: an article he wrote about alleged corruption in the office of the president.

The Cybercrime Act was introduced to combat a growing trend of internet fraud and other criminal activity within Nigeria, but it has instead frequently been used to suppress journalism published online. One provision in particular—Section 24, which made it illegal to publish false information online that was deemed to be “grossly offensive,” “indecent,” or even merely an “annoyance”—has been especially ripe for abuse. In 2019, for instance, Agba Jalingo, a journalist and publisher of CrossRiverWatch, in Nigeria’s Cross River State, was arrested and charged under Section 24 after he published articles accusing the state’s governor of corruption. (He was later acquitted.) In February 2024, Nigerian lawmakers amended Section 24 to remove some of its most egregious elements, but the new language still makes it illegal, and punishable by up to three years in jail, to “knowingly or intentionally” communicate online anything that is “false, for the purpose of causing a breakdown of law and order [or] posing a threat to life.”

“This vague text is still used to unfairly prosecute journalists, particularly those who regularly publish investigative reports implicating political or institutional forces,” said Sadibou Marong, the sub-Saharan Africa bureau director of Reporters Without Borders. “Authorities are intent on gagging investigative journalism uncovering corruption and governance issues in the country. The continued implementation of this law constitutes a real threat.”

Loosely linked:

India’s powerful turn to lawfare to stifule the press by Vidya Krishnan for Nieman Reports.

TikTok gets its Indonesian operating license back after giving government data from protests by Niniek Karmini for AP.

China’s Cyberspace Administration is suppressing “pessimistic and negative sentiments” online by Oiwan Lam for Global Voices.

Social media content restricted in Afghanistan, Taliban sources confirm by Hafizullah Maroof and Doug Faulkner for BBC.

Write a bad review of Taylor Swift and get death threats: Inside the fan backlash facing critics in the digital age by Gretel Kahn for RISJ.

Other curious links, including en español et français

LONG READ | The Pushkin job: unmasking the thieves behind an international rare books heist by Philip Oltermann for The Guardian.

INVESTIGATIVE | Wildfires ravage one of Africa’s largest nature reserves by Merel Zoet and Aiganysh Aidarbekova for Bellingcat.

PHOTO ESSAY | Two years of displacement and destruction in Gaza by Enas Tantesh for The Guardian.

El 10 por ciento de los médicos y las enfermeras han tenido ideas suicidas: amenazas, agresiones y acoso sexual en el trabajo por Fran Sánchez Becerril en El Confidencial.

Aborto, ¿un derecho en peligro? por Nuria Alabao en CTXT.

Cómo han aumentado las protestas mundiales a favor de Palestina en los últimos meses: España, entre los 10 primeros por Icíar Gutiérrez e Yuly Jara en elDiario.es.

Lutte contre la pédocriminalité ou surveillance généralisée ? Cinq questions sur le projet de règlement européen surnommé Chat Control par Luc Chagnon dans Franceinfo.

Du smartphone au sextoy : pourquoi tous les guides d’achat des médias ne se valent pas par Vincent Bresson dans La revue des médias.

Gaza, Ukraine : comment des anonymes aident les journalistes à vérifier les images de la guerre par Tom Sallenbien dans La revue des médias.

What I read, listen, and watch

I’m reading Spin Doctors (2021) by Nora Loreto about the misdiagnosis of the COVID-19 pandemic by the media and politicians.

I’m listening to Nature’s podcast on how stereotypes shape AI and what that means for the future of hiring.

I’m watching SCMP’s piece on the Gen Z social media users turning against Asia’s richest.

Chart of the week

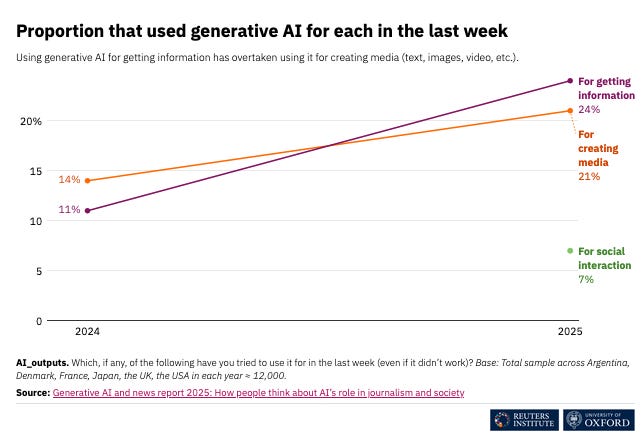

RISJ study shows an increase in the number of respondents from six countries (n ≈ 12,000) who use generative AI to get the news. Among those who do, the most common use is asking for the latest news (54 per cent) and following up about a news story (47 per cent). On average, most respondents trust ChatGPT, Google Gemini and Microsot Copilot.

Perceptive and insightful, thanks for sharing your thoughts.