The 237th Block: Climate communication, and others

It's sweater weather in the middle of November in Toronto, good for me, bad for me!

This week…

Your reading time is about 5 minutes. Let’s start.

The UK’s Guardian, Spain’s La Vanguardia, and a German football club, St Pauli, quit the “disinformation network,” also known as X, formally known as Twitter. Social media, it seems, lacks established “regulations that protect reliable sources of information on digital platforms,” per RSF.

Your Wikipedia this week: Betteridge’s law of headlines

Hey, by the way, remember in #226 when the Scunthorpe problem sparked the ‘Wikipedia this week’ section? Here’s one Scunthorpe problem, which affected the town of Coulsdon. Can you guess why?

And now, a selection of top stories on my radar, a few personal recommendations, and the chart of the week.

ICYMI: The Previous Block was about the broligarchy. FWIW:

The disturbing rise of tech-bro pronatalism by Sarah Manavis for The New Statesman.

The cultural power of the anti-woke tech bro by Rebecca Jennings for Vox.

CORRECTION NOTICE: None notified.ON MEDIA REGULATION

‘I was moderating hundreds of horrific and traumatising videos’

Zoe Kleinman for BBC:

Beheadings, mass killings, child abuse, hate speech—all of it ends up in the inboxes of a global army of content moderators.

You don’t often see or hear from them—but these are the people whose job it is to review and then, when necessary, delete content that either gets reported by other users, or is automatically flagged by tech tools.

The issue of online safety has become increasingly prominent, with tech firms under more pressure to swiftly remove harmful material.

And despite a lot of research and investment pouring into tech solutions to help, ultimately for now, it’s still largely human moderators who have the final say.

Moderators are often employed by third-party companies, but they work on content posted directly on to the big social networks including Instagram, TikTok and Facebook.

Loosely linked:

Ugandan TikTokers held for insulting first family by Basillioh Rukanga for BBC.

How the Australian government’s misinformation bill might impede freedom of speech by Anne Twomey (University of Sydney) for The Conversation.

How China sought to censor news of deadly Zhuhai car attack by Mary Yang for HKFP with AFP.

China’s queer influencers thrive despite growing LGBTQ+ censorship ($) by Stephanie Yang and Xin-yun Wu for LA Times.

ON LANGUAGE

Can AI review the scientific literature—and figure out what it all means?

Helen Pearson for Nature:

Some of the newer AI-powered science search engines can already help people to produce narrative literature reviews—a written tour of studies—by finding, sorting and summarising publications. But they can’t yet produce a high-quality review by themselves. The toughest challenge of all is the ‘gold-standard’ systematic review, which involves stringent procedures to search and assess papers, and often a meta-analysis to synthesise the results. Most researchers agree that these are a long way from being fully automated. “I’m sure we’ll eventually get there,” says Paul Glasziou, a specialist in evidence and systematic reviews at Bond University in Gold Coast, Australia. “I just can’t tell you whether that’s 10 years away or 100 years away.”

Loosely linked:

AI won’t protect endangered languages by Ross Perlin for The Dial.

Can AI replace translators? by Keza MacDonald for The Guardian.

AI models work together faster when they speak their own language by Matthew Sparkes for New Scientist.

Death in grammar by Teresa Grøtan (translated by Caroline Waight) for The Dial.

France’s new dictionary struggles to keep up with the times by Hugh Schofield for BBC.

What I gained (and lost) as a native Chinese writing in English ($) by Lija Zhang for SCMP.

ON THE CLIMATE

Climate science is getting lost in translation

Anna Turns for The Conversation:

Understanding complex climate science can be tricky enough, even in your own language. So what happens when none of the mainstream climate information is published in your native tongue?

Most people are excluded from conversations and decisions about how to tackle the biggest threat to humanity because they can’t easily access accurate reporting.

Almost 90% of scientific publications are in English, explains Marco Saraceni, a professor of linguistics at the University of Portsmouth. “This is a staggering dominance of just one language. But English, often called a global language, is only spoken by a minority of the world’s population.”

Between 1 and 2 billion people speak English—so, as Saraceni highlights: “At least three-quarters of the world’s population do not speak the language in which the science about climate change is disseminated globally. At the same time, languages other than English are marginalised and struggle to find space in the global communication of science.”

Loosely linked:

The people cracking the world’s toughest climate words by Francis Agustin for BBC.

How we developed sign language for ten of the trickiest climate change terms by Audrey Cameron (University of Edinburgh) for The Conversation.

Separating religion from climate communication leads to failure by Kristian Noll for LSE Blogs.

Big Tech enables climate disinformation, CAAD report finds by Ricky Lee for Tech Informed. The CAAD report is accessible here.

Other curious links, including en español et français

LONG READ | The inspiring scientists who saved the world’s first seed bank by Simon Parkin for The Guardian. This is an extract from the author’s book The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad. By the way, in a #198 long-form I wrote a while back, a portion of it was also bout the scientists in the besieged Leningrad.

INFOGRAPHIC | Visualising the war in Sudan: Conflict, control and displacement by Mohammed Hussein for Al Jazeera.

PHOTO ESSAY | How the Taliban are erasing Afghanistan’s women by Mélissa Cornet and photography by Kiana Hayeri for The Guardian.

Germany's ‘wall in the head’ is coming down by Benedict Vigers and John Reimnitz for Gallup.

Francesca Albanese: This Is genocide by Owen Dowling for Jacobin.

Sheinbaum contra el ‘lawfare’: La reforma judicial de la nueva presidenta se topa con las críticas de la izquierda liberal, que la tacha de autoritaria por Andy Robinson en CTXT.

El juguete favorito de la política es un jarrón chino que Elon Musk no puede romper por M. Mcloughlin en El Confidencial.

Un grupo de figurantes se niega a que les escaneen en un rodaje sin avisar por Laura García Higueras en elDiario.es.

Courriels oppressants, propositions de rendez-vous ou micro-agressions : le sexisme passe aussi par les mails professionnels, d'après une étude par Camille Laurent dans France Info.

Google va arrêter les publicités politiques en Europe, car le cadre légal est jugé trop complexe par Hugo Bernard dans Numerama.

Le collectif Montréal antifasciste dénonce un festival de musique black métal par Sam Harper dans Pivot.

What I read, listen, and watch

I’m reading The Empress of Salt and Fortune (2020) by Nghi Vo. Sometimes you just need a little bit of fantastical escapism.

I’m listening to “Locate Your Nearest X-it" on Ctrl-Alt-Speech.

I’m watching NatGeo’s “Kingdom of the Kims: Rise to Power,” a look inside North Korea’s dynasty.

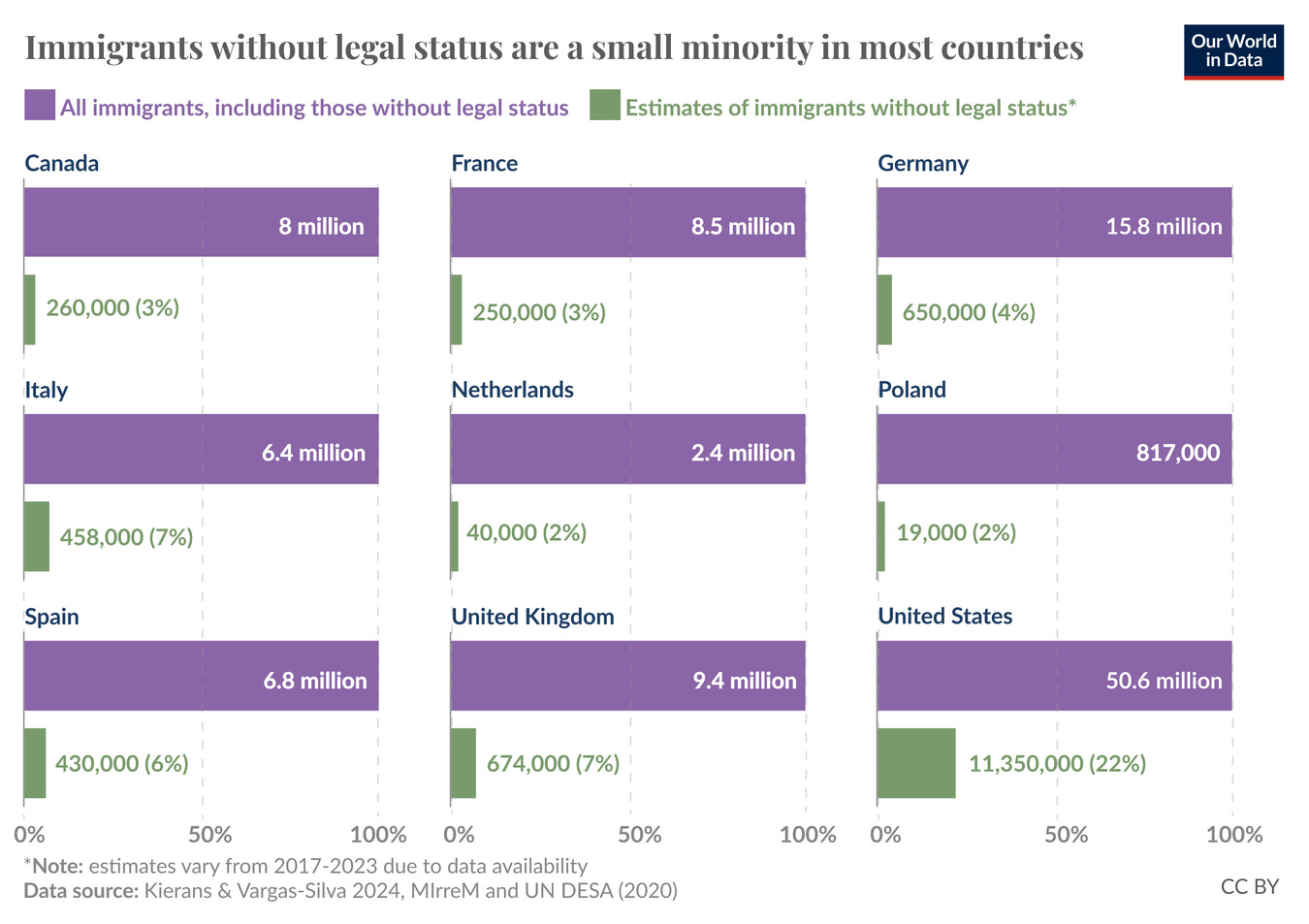

Chart of the week

Immigrants without legal status are a small minority in most countries, according to this piece by Simon van Teutem and Tuna Acisu for Our World In Data.