This week…

Your reading time is about 11 minutes. Buckle up.

I attended a talk on artificial intelligence and academic integrity with speakers from Brock University. The three speakers, Rahul Kumar, Michael Mindzak, and Sunaina Sharma, touched on the technical, philosophical, and practical aspects of the subject.

On the way to the talk, I speculated about what might be brought up:

First, the human ego will always make us believe we are not gullible, that we have superior AI literacy.

Second, educators will find a way to work around students’ use of AI chatbots in the classroom, I don’t know exactly how, but I’m sure of it (hello, ego).

And third, mainstream AI will change our language mastery and communication.

Let’s go through each of them, and I’ll explain if they were addressed during the talk, and how.

We can always tell

I know what it sounds like. Bear with me briefly; I am not equating you with transphobes, but we can learn something from them. The “we-can-always-tell” transphobe brigade insists they can always tell if someone is trans, then proceeds to use images of swimmer Katie Ledecky, or singer Pink, or actress Zendaya unironically to prove themselves (wrong). If anything, it tells you how thin the line that separates transphobia and misogyny (and particularly, misogynoir) is.

The same is true with chatbot-generated writing; we can’t always tell. Here are some non-AI scenarios to consider, where teachers cannot always tell when an assignment is written by their students:

AAVE users don’t always write how they talk. They may write in the English you want them to — to get those good grades from you.

ESL speakers may not be as confident with their speaking skills as they are with their writing skills. This is true for some monolingual English speakers too.

Students have been wrongly accused of cheating. Sometimes, it’s “collateral damage” because there are actual large-scale cheating operations (Amelia Gentleman, The Guardian); other times, it’s xenophobia (Jenny Abamu, WAMU).

Was this addressed during the talk? Yes.

In the interactive part of the talk, we were presented with three texts that responded to the same prompt. Only one was written by a human. We had to choose which one we thought it was and why. I chose one — at random. I never claimed I could tell machine writing and human writing apart. It was as good as a coin toss if a coin has three sides.

One person said Text A was longwinded, like herself; thus, it’s human-generated. Another person said he chose Text B because it was descriptive and not a definition, while someone else said that he chose Text C precisely because it was a definition, not a description. In other words, nobody knows what parameters to use to decide what’s human and what’s not, because they’re all valid.

The speakers also mentioned that AI chatbot detectors have been unreliable. There are obvious false positives, such as when GPTZero claimed that 92 per cent of the US Constitution was written by AI, as pointed out by William LeGate, and several others. The StealthGPT team also showed that another AI text detector, Originality.ai, flagged the bible as 99 per cent AI-generated.

We think we are smarter than machines

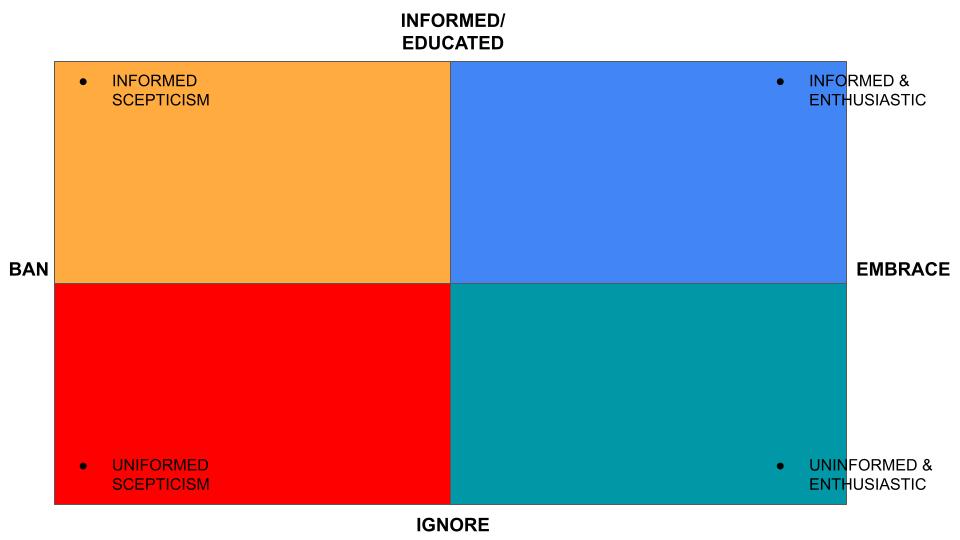

So, if we can’t always tell, then what are we going to do about AI and academic integrity? Ban it? Embrace it? Students will use AI chatbots anyway, whether it is allowed or not. Pardon my crude reproduction of the diagram from the speakers’ presentation, but whatever option you choose, you could likely plot yourself somewhere in the chart below. It was attributed to Lancaster (2023), who I assume is Thomas Lancaster, and Kumar (2023), who I assume is one of the speakers.

Before the talk, I postulated that AI chatbots would find their place in the classrooms in a legitimate way, the same way the calculator did. If I recall correctly, for the first nine or so years in school, we didn’t use the calculator in class, in Malaysia, at least. We were only allowed to use it in the upper secondary onwards, where math problems were presented in such a way that students must first be able to demonstrate that they understand and, thus, could translate the text problem into a mathematical expression. The process was assessed (i.e. “show your work”), not just the product.

For example, if I was paid $235 for a day where I worked seven hours, how much would I make in a fortnight if I worked a total of 37.5 hours a week? To solve this problem, you must first be able to write out the problem in a mathematical equation to key that into a calculator to get the answer: 235/7 × 37.5 × 2 = 2517.85.

Now, you will no longer need to understand a worded problem to translate it into an equation; the AI chatbot will do it all for you. So, how will school assessments evolve? I wasn’t sure how, but I was sure that someone had already thought about it.

Was this addressed during the talk? Yes, to my delight, a math example was used.

In a case study, a math teacher presented his class with the following problem: A piece of wire 10 m long is cut into two pieces. One piece is bent into a square, and the other into a circle. How should the wire be cut so that the total area enclosed is a maximum? (I reproduced this from memory, so it might not be accurate, but that’s inconsequential.)

The assignment was to input this problem into ChatGPT, and based on the response, the students needed to explain why ChatGPT’s answer was accepted or not. The students showed that ChatGPT’s suggestion was not ideal and devised a much better solution. (There was another case study from an English class in Costa Rica, but I don’t recall the details. However, it proved the same thing, that students found that they could improve on ChatGPT’s response to get better grades.)

The most kiasu students will always find a way to prove that they are better than machines, and that’s very human of us. AI chatbots can have a place in the classroom; educators need to know when and how to include them. This brings us to my final point.

English is the most important programming language

I’m sure you’ve read iterations of this saying on LinkedIn, Reddit or Twitter. You can get AI chatbots to write codes in any programming language you wish, even if you have no knowledge of it, as long as you know how to write the prompts.

Surely you have also heard about how prompt writer or prompt engineer jobs are the next big thing, boasting six-figure salaries. (Technically, I could say I have at least three years of experience in prompt writing, as I have even produced one edition of The Starting Block that was written by GPT back in 2020.)

Yet writing a good prompt is not as easy as you think. Anyone can take photographs, yet not everyone will be a good photographer. And anyone can write, but not everyone will be a good author. Similarly, anyone can use AI chatbots; not everyone will be good prompters. Additionally, just like many popular search engines, most AI chatbots work best with English. That could widen the language gap in diverse classrooms like Canada’s, especially without the necessary support for AI literacy, on top of English language literacy.

Plus, it’s not just a matter of language mastery; it’s a matter of understanding the logical operations of the service. For example, there are many ways to improve your search results when using search engines (e.g. quotations for specific phrases, hyphens to exclude words, colon to search specific sites, asterisk as a placeholder, OR operator to return multiple results, ellipsis to search a range of numbers, etc.). Yet, most people still do not use them effectively — or at all.

I wondered if the proliferation of AI chatbot usage would change communication styles since you must be precise with your prompts by specifying context, tone, audience, etc. Will this neutralise the effects of using virtual assistants such as Siri and Alexa, which are reportedly causing kids to be terse, even rude (Amelia Hill, The Guardian)?

Was this addressed during the talk? Not during the presentation, but I fed the question during the Q&A session so that the speakers could bring up prompt optimisers, which they did.

Prompt optimisers, such as Perfect Prompt, are AI-based services where you can input your raw prompts to generate higher-quality prompts that you can feed into your AI chatbot of choice. So you don’t necessarily need to have a good command of the language to maximise your AI chatbot use, because there is an AI service for that — to no one’s surprise.

Most generative artificial intelligence programs are text-to-text, text-to-image, and text-to-audio. However, the next big thing, according to the speakers, is probably speech-to-text models, which may be most beneficial for spec ed needs. Personally, I am looking forward to an image-to-image model. I am hoping that I will be able to draw squiggly lines and curves and the AI service will be able to produce a higher-quality version of my doodles. That way, I can be a fashion designer without knowing how to actually draw or describe with words what I have in mind since I don’t have the technical vocabulary.

One thing that was unfortunately not addressed during the presentation or Q&A session was the ‘grandma’ jailbreak, role-playing, and other ways users have tried to and succeeded in working around AI chatbot safeguards, which prevent the unethical use of their services. Please find more on this in the reading list below.

In summary, we need to improve our AI chatbot literacy to preserve academic integrity. Coming from a family of educators and having married an educator who also comes from a family of educators, I know one thing about teachers: You can probably trick them once, maybe even twice, but sooner or later, they will catch on to what’s going on, and their students will learn their lessons one way or another.

And now, a selection of top stories on my radar, a few personal recommendations, and the chart of the week.

AI spam is already flooding the Internet and it has an obvious tell

Matthew Gault for Vice:

Those two phrases, “as an AI language model” and “I cannot generate inappropriate content,” recur so frequently in ChatGPT generated content that they’ve become memes. These terms can reasonably be used to identify lazily executed ChatGPT spam by searching for them across the internet.

AI translation is jeopardizing Afghan asylum claims

Andrew Deck for Rest of World:

A U.S. court had denied the refugee’s asylum bid because her written application didn’t match the story told in the initial interviews. In the interviews, the refugee had first maintained that she’d made it through one particular event alone, but the written statement seemed to reference other people with her at the time — a discrepancy large enough for a judge to reject her asylum claim.

After [Uma Mirkhail] went over the documents, she saw what had gone wrong: An automated translation tool had swapped the “I” pronouns in the woman’s statement to “we.”

I interviewed a breast-cancer survivor who wanted me to tell her story. She was actually an AI.

Julia Pugachevsky for Insider:

Next time, “Kimberly Shaw” might wave to me over video or sound convincingly passionate over the phone. I’m preparing for the day she does.

What I read, listen, and watch…

I’m reading Reuben Cohn-Gordon’s essay on GPT’s inhuman mind on Noema.

I’m listening to Tech Won’t Save Us, hosted by Paris Marx. In this episode, Aaron Benanav explains why chatbots won’t take many jobs.

I’m watching South Park’s “Deep Learning” episode. The episode, written by ChatGPT, is about using ChatGPT in school and dating. It was recommended by Michael Mindzak, one of the speakers at the talk I attended.

Reviews, opinion pieces, and other stray links:

We tested a new ChatGPT-detector for teachers. It flagged an innocent student by Geoffrey A. Fowler for WaPo.

Sidestepping ChatGPT’s guardrails ‘like a video game’ for jailbreak enthusiasts—despite real-world dangers by Rachel Metz and Bloomberg on Fortune.

Detailed jailbreak gets ChatGPT to write wildly explicit smut by Maggie Harrison for Futurism.

Standardized tests are failing English language learner students, according to educators and academics by Muzna Erum for New Canadian Media.

How to perfect your prompt writing for ChatGPT, Midjourney and other AI generators by Marcel Scharth for The Conversation.

You’re wrong about Gen Z by Stephanie Bai for Maclean’s.

Chart of the week

On March 27, OpenAI released a technical report that included a set of exam results taken by GPT-4. Visual Capitalist’s Marcus Lu and Rosey Eason charted how smart ChatGPT is based on this report. The text version can be found here.

And one more thing

For someone who likes to talk about how the printing press democratises knowledge, I did not know Johannes Gutenberg was inspired by... the grape press.

This is some top quality stuff. There will always be issues with academic integrity, before AI was ever in the frame. Plagiarism for example. AI is here to stay. The education sistem will evolve, it will adapt.

At this point who hasn't used chatgpt to get work done anyway. If you don't, your loss!