The 126th Block: Social engineering

How A/B testings can be a form of questionable social engineering

This week…

To prep yourself for the content of this edition, here’s the opening paragraph from Wikipedia’s entry on social engineering (political science):

Social engineering is a top-down effort to influence particular attitudes and social behaviors on a large scale—most often undertaken by governments, but also carried out by media, academia or private groups—in order to produce desired characteristics in a target population. Social engineering can also be understood philosophically as a deterministic phenomenon where the intentions and goals of the architects of the new social construct are realized. Some social engineers use the scientific method to analyze and understand social systems in order to design the appropriate methods to achieve the desired results in the human subjects.

Not to be confused with social engineering (security):

In the context of information security, social engineering is the psychological manipulation of people into performing actions or divulging confidential information. This differs from social engineering within the social sciences, which does not concern the divulging of confidential information. A type of confidence trick for the purpose of information gathering, fraud, or system access, it differs from a traditional “con” in that it is often one of many steps in a more complex fraud scheme. It has also been defined as “any act that influences a person to take an action that may or may not be in their best interests.”

Okay, ready? Now, a selection of top stories on my radar, a few personal recommendations, and the chart of the week.

LinkedIn ran social experiments on 20 Million users over five years ($)

Natasha Singer for NYT:

In experiments conducted around the world from 2015 to 2019, LinkedIn randomly varied the proportion of weak and strong contacts suggested by its “People You May Know” algorithm — the company’s automated system for recommending new connections to its users. The tests were detailed in a study published this month in the journal Science and co-authored by researchers at LinkedIn, M.I.T., Stanford and Harvard Business School.

LinkedIn’s algorithmic experiments may come as a surprise to millions of people because the company did not inform users that the tests were underway.

Tech giants like LinkedIn, the world’s largest professional network, routinely run large-scale experiments in which they try out different versions of app features, web designs and algorithms on different people. The longstanding practice, called A/B testing, is intended to improve consumers’ experiences and keep them engaged, which helps the companies make money through premium membership fees or advertising. Users often have no idea that companies are running the tests on them.

Reread that last sentence.

But the changes made by LinkedIn are indicative of how such tweaks to widely used algorithms can become social engineering experiments with potentially life-altering consequences for many people. Experts who study the societal impacts of computing said conducting long, large-scale experiments on people that could affect their job prospects, in ways that are invisible to them, raised questions about industry transparency and research oversight.

“The findings suggest that some users had better access to job opportunities or a meaningful difference in access to job opportunities,” said Michael Zimmer, an associate professor of computer science and the director of the Center for Data, Ethics and Society at Marquette University. “These are the kind of long-term consequences that need to be contemplated when we think of the ethics of engaging in this kind of big data research.”

The main thing LinkedIn wants us to take away from this is probably the findings that show that relatively weak social connections were more helpful in findings jobs than stronger social ties.

Discerning critics, such as Charles Arthur, may offer the following observation:

Exactly like the Facebook “study” in 2014, when more than half a million users had their News Feeds manipulated to see if positive emotions begat positive posts, and negative ones begat gloomier ones. (They do.) Like LinkedIn now, Facebook claimed then it was covered by its Ts and Cs. (Very questionable claim, both times.) Social media sites seem unable to let go of the power they have to do seemingly trivial things like this. They couldn’t recruit people properly into a double-blind trial? No, of course not.

Courtney Vinopal compiles a few more expert views for Observer.

As a side note, if anyone can provide the full text to the study for me, I’d be forever indebted.

How Science Friday used A/B testing to guide audience engagement

When the pandemic began, Science Friday “had to rethink how we engaged with audiences interested in science.” In particular, they had to consider the following: “How could we shift our radio, educational, and event programming to fulfil science educational gaps and activate new C*Science volunteers?” C*Science is Science Friday’s program for nonprofessional scientists to participate in scientific research, also known as citizen science, community science, or crowd-sourced science. Science Friday’s manager of impact strategy Nahima Ahmed writes a comprehensive report on their findings.

What I read, listen, and watch…

I’m reading how data journalism hasn’t changed that much in four years by Laura Hazard Owen for Nieman Lab.

I’m listening to an episode of In Machine We Trust about digital twins of humans capturing the physical look and expressions of real humans.

I’m watching This England, dramatised version of the UK’s first wave of COVID-19 in a six-part docudrama series.

Reviews, opinion pieces and other stray links:

“When was the last time a single title was being dissected by everyone you know?” Podcasting is just radio now, declares Nicholas Quah on Vulture.

Actor Bruce Willis becomes first celebrity to sell rights to deepfake firm by Tamera Jones for Collider. UPDATED: Bruce Willis’ rep refutes the claim (Ryan Gajewski, The Hollywood Reporter).

From

the archives, well,2021: How the New York Times A/B tests their headlines by Tom Cleveland for TJCX.

Chart of the week

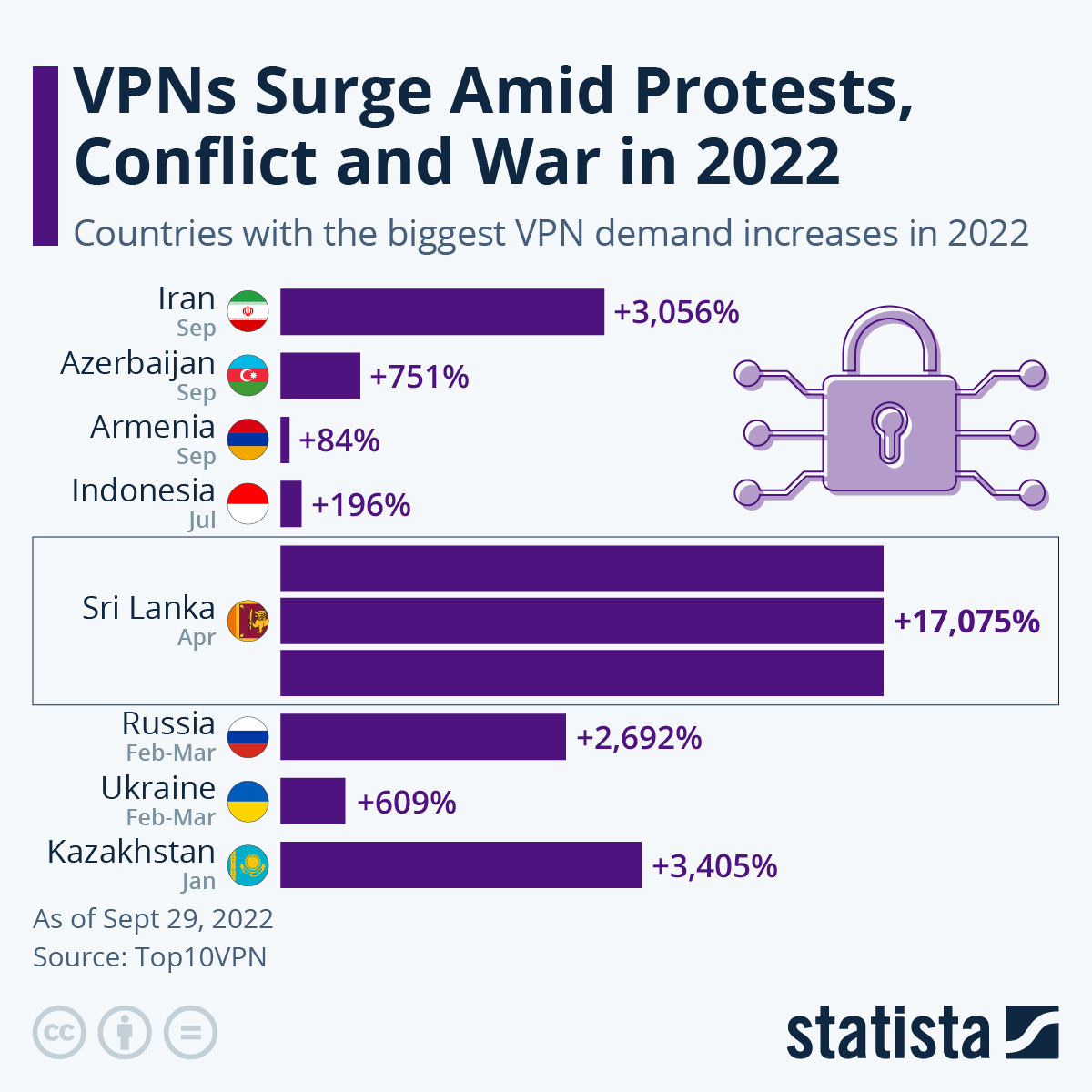

VPNs surge amid protests, conflict and war in 2022, reports Anna Fleck for Statista. The chart shows countries with the biggest VPN demand increases as of September 29, 2022, based on numbers from Top10VPN. Sri Lanka records a 17,075 per cent increase, followed by Kazakhstan (3,405 per cent) and Iran (3,056 per cent). In Russia, demands for VPN increased by 2,692 per cent, while in Ukraine, it is 609 per cent.

VPNs don’t work when countries shut off the Internet completely. Iran has shut down WhatsApp and Instagram following recent nationwide discontent over the death of Mahsa Amini who was arrested by morality police for not wearing the hijab based on government standards.

And one more thing

Spacetime is a social construct. (Ps. Most Twitter threads are useless; this one isn’t.)