The 117th Block: Against poor reporting and 'poor' reporting

And dangerous reporting and irresponsible reporting

This week…

Earlier in the week, I became irate at how some reporters covered the chess robot incident. That felt like a long time ago. There’s a succinct article by the CBC to fill you in. However, there is also a bad TV segment on a CBC programme, Canada Tonight, which starts at the 44:38 mark.

Throughout that whole day, I monitored how the story was reported, and that evening TV programme tipped me over the edge just because of how callously the story was presented. Many may not consider it to be bad—that the elements of sensationalism or scare tactics are mild. Of course, it certainly pales compared to some of the more bizarre news we have consumed since the ‘post-truth era’—whether it is pizzagate, or whatever else.

But let me point out what sandwiched this particular TV segment. At the top of the story: “Here’s a cautionary tale about the rise of technology.”

And the tail: “Sounds like the beginning of a horror movie.”

Let’s step back for a moment. If I were to report about a crash at a traffic light intersection and preface and postface the piece with similar embellishments, what exactly am I cautioning you about? Am I suggesting we should go back to horses and carriages? That we shouldn’t trust traffic lights? That we should make our own judgment when crossing the road, ignoring the lights?

Now, back to the chess robot story. What uprising are we contending with here exactly? Why is a chess robot scary? The robot does not have its own mind; you wait your turn, and sometimes you get into an accident, like a traffic collision. We do not proceed to scare the audience about traffic technology subliminally. Neither should we cause panic about robotics.

Producers and journalists putting that angle on the chess robot story are irresponsible and more dangerous than the chess robot. You do not have to understand the technology, but you have to make an effort not to forward your ignorance in the story’s treatment.

More similar incidents, particularly in AI and ML reporting, are creating this slow decline in trust in public communication about technology. All because of news readers from major news outlets with their star-studded award-winning production members who don’t do better.

Then there will come a time when technology has its own version of the coronavirus pandemic. And we are going to wonder why public policy measures fail. Now, remember that the public communication fallout exacerbated the early pandemic response. Years and years of poor health ‘news’ by quacks like Oprah, Oz, and Phil made people think they know better than credible experts.

We have learned absolutely nothing.

While writing this, I am reminded of a study about how UK media cover artificial intelligence, which Scott Brennan presented at Wolfson College during my press fellowship. That was three years ago, but I think not much has changed. For instance, AI is still “a term both widely used and loosely defined.” And then this citation:

Others have argued that media coverage frequently swings between two sensational poles: utopian dreams of workless futures and eternal life, and dystopian nightmares of robot uprisings and the apocalypse (Claire Craig, 2018).

There was also a lot of pope-aganda in the Canadian media, but that’s for another day. Now, for the rest of this newsletter, a selection of top stories on my radar, a few personal recommendations, and the chart of the week.

Against ‘poor’ reporting

Alissa Quart for CJR:

One of the phrases that most offends Heather Bryant, a former reporter and director of the Tiny News Collective, is “unskilled worker,” variations of which are easy to find in day-to-day media coverage. To Bryant—who grew up in “deep, deep poverty” in rural Missouri, and whose family experienced the sting of stigmatizing coverage—such phrases simultaneously take the dignity out of work and normalize class prejudice, implying that people who work demanding jobs are underpaid for their labors because they are lacking in skill. The insinuation of this idiom is that “skill” is narrowed and reduced, for instance, to jobs that require a college degree, the lack of which might be an alibi for an employer to pay a worker an exploitative wage. “If the job provided no value in the grander scheme of things,” Bryant says, “it wouldn’t exist.”

The idea of some workers being “unskilled” is part of a media industry mindset that, Bryant believes, limits who reporters interview, and to what end. “We should be talking to people across a wide spectrum of circumstances,” Bryant says, and quoting such sources “for stories beyond the coverage of their specific circumstances, because they all have different, valuable perspectives on any issue.” Instead, working-class and financially stressed people are often featured in coverage that otherizes or minimizes them.

Empathetic verification: how did Norwegian newsrooms cover ‘Long COVID’?

Hanne Østli Jakobsen for Reuters Institute:

Between January 2020 and March 2022, the three large Norwegian media outlets Aftenposten, VG and NRK’s online edition published (at least) 129 articles about or mentioning Long COVID. The stories reveal some interesting patterns in how we’ve reported on Long COVID:

More than a third – 36% – of Long COVID articles featured a patient narrative or a “case” (the term used in Norwegian): a meeting with someone who is struggling with long-term effects after being sick.

Long COVID is more commonly reported by women. And yet, 53% of the patients featured in Norwegian Long COVID stories were men.

Of the patients featured in these stories, 60% were suffering from Long COVID after having a mild case of COVID – they were never in hospital.

85 different symptoms have been linked to Long COVID by patients, researchers or other sources.

Only once has a journalist followed up with a patient: the patient was getting married – he had proposed while hospitalised – and NRK covered the wedding. Otherwise, we don’t know what happened to these patients. Did they get better? Still struggling? As of this writing, the reporting doesn’t say.

Where are the immigrants?

Long COVID sufferers, as portrayed by these three outlets, are white Norwegians: 41 out of the 46 Norwegian Long COVID patients profiled in these articles were ethnic majority Norwegians (as identified by photos and by names like Ingrid, Svein, Åse).

That’s 89.1% representation for 83% of the population. Contrast that with the fact that people with immigrant backgrounds were almost three times as likely to get infected by the coronavirus and almost four times as likely to end up in hospital. Why aren’t journalists talking to them?

Revisiting warnings that stigmatising language undermines MPX response

22 May 2022—UNAIDS warns that stigmatising language on monkeypox jeopardises public health. “UNAIDS has expressed concern that some public reporting and commentary on Monkeypox has used language and imagery, particularly portrayals of LGBTI and African people, that reinforce homophobic and racist stereotypes and exacerbate stigma. Lessons from the AIDS response show that stigma and blame directed at certain groups of people can rapidly undermine outbreak response.”

5 June 2022—The Guardian [editorial] view on monkeypox: communication is crucial. “Monkeypox […] spreads from animals to humans, with a name that originates from its first discovery in monkeys in a Danish laboratory in 1958. It is, in fact, more likely to have come from rodents, from eating undercooked and infected meat, and from handling infected fur or animal skins. Its transmission between humans is predominantly via close contact, which is why it spreads through sex. However, it is not a sexually transmitted disease, but a virus that can also be spread by coughing, sharing linen, or touching infected skin. Its exotic-sounding name is neither accurate nor helpful.”

30 July 2022—In Spain, physician Dr Arturo M Henriques B shares, in an unverified Twitter thread, a sighting of a person with infectious MPX lesions on a public transport. He claims he does not need to quarantine because he won’t touch anyone’s testicles, while a passenger nearby says she is not afraid because she is not gay. Spain has 4,298 MPX cases and two deaths as of July 30th.

What I read, watch, and listen to…

I’m reading about the people of the cloud by cloud anthropologist Steven Gonzalez Monserrate for Aeon.

I’m watching Everything Everywhere All At Once. Very good.

I’m also watching the UEFA Women’s Euro final. Record-breaking attendance! Record-breaking total viewership for the tournament!

Reviews, opinion pieces and other stray links:

The world needs uncles, too by Isaac Fitzgerald for Esquire. Yes we do.

LGBTQuiet? Silence does not mean consent by Terri Teo for New Mandala.

Where too many have gone bofore: Trauma in Voyager by Wendy Jones for Psychology Today. Marrying Star Trek and psychology? Why, yes.

Chart of the week

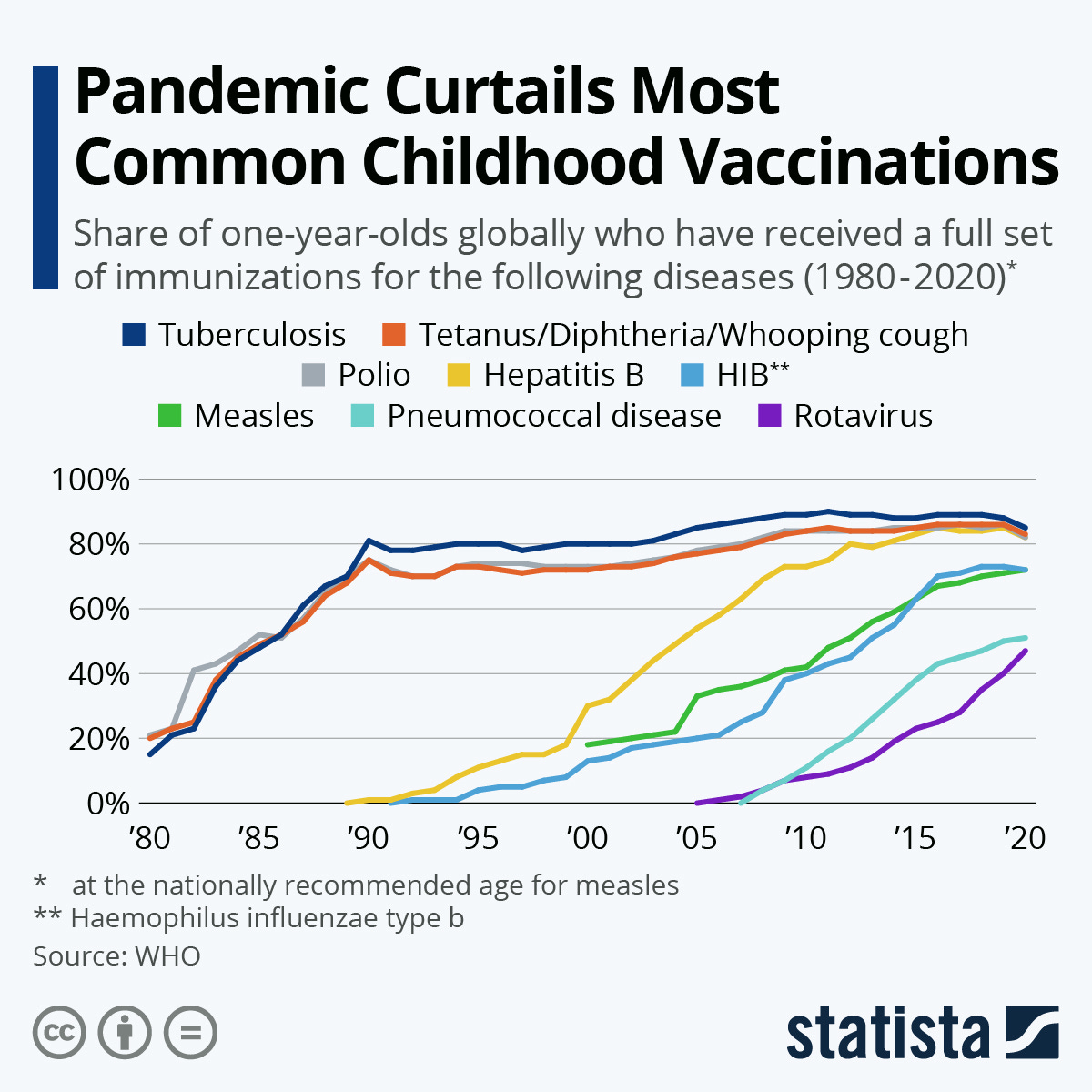

On Statista, Katharina Buchholz writes that the pandemic curtails most common childhood vaccinations. The link takes you to the text version of the chart.

A friend sent this to me man, it's so true cbc more like cbshit

Canadian media going downhill, Cbc Ctv all the same.