The Sidelines: Is paying a premium more expensive than giving up personal data?

With Emmanuel Olalere, content creator

The Sidelines is the supplementary issue to every main edition of The Starting Block. Here you will find the interview transcript and more information about the conversation of the week. The interview is transcribed by Otter.ai and edited for length and clarity. All links provided come from me, and not the guest, unless stated.

Listen to the audio version here.

TRANSCRIPT

TINA CARMILLIA: Hello, my name is Tina Carmillia and this is The Starting Block, a weekly conversation on science and society with an emphasis on disinformation, data, and democracy.

Before we start, I’d like to let you know that the transcript and credits for this conversation are available on The Sidelines, the supplement to every main edition of The Starting Block.

Now, in the next lane: Emmanuel Olalere, a tech and lifestyle-focused content creator. In this first part of our conversation, we’ll focus on the lifestyle side, and we’ll get some reviews of the trends and news that made the headlines this month.

Ready? Let’s go.

Who is Emmanuel and is he the same as his online persona that we all get to see?

EMMANUEL OLALERE: In many ways it is quite funny when you ask that question, because also like there’s been Emmanuel 1.0 and 2.0 and 3.0. So there’s been many evolutions but currently right as I am, I would say I’m a content creator who is also an avid runner who likes to—whether it’s through the medium of photos or videos or words or it doesn’t really matter—I just love being in a creative space where I believe that creativity is not just in the arts. You can be creative in anything.

TINA CARMILLIA: But what does it mean to be an online creator? How long have you been doing this? Is this something that you’ve always wanted to do?

EMMANUEL OLALERE: It’s been a while I think since 2007. So I started initially as a programmer. I started coding out of high school, for I think, three, four years in high school and out of high school. I’ve always been this kind of a person where I’d like to take things apart, right? So if I get a new tech, I’d always take it apart, look at what is inside. And I grew up in a kampung—so for our international audiences, that’s like a village. So I grew up in a literal village. So it was very weird seeing this guy, who grew up in the village obsessed about all the tech stuff. I used to travel to actually go buy tech magazines like T3.

So, one thing that I noticed—and I think that was what led me to my creative journey— was that many people used to ask me like a lot about many things like, “Emmanuel, how do you do this?” “Emmanuel, how do you do that?”

TINA CARMILLIA: You’re the tech support.

EMMANUEL OLALERE: I know! I’ve always been the tech support, right. So, when I came out of high school, everybody goes to college immediately, but I didn’t want to. If anything, I was not interested in college at all. Instead of going to college I actually went to a computer centre, where I learned Java programming, I learned how to be a programmer. And it was during that time when one of my friends was like, “Hey man, will you teach me how to open a blog?” And I was like, “Yeah, you just go to blogspot.com.” He’s like, “No, but I want you to do it.”

I think it’s at that moment I learned the value of assigning monetary value to what you know, like, knowledge is power slash money, right? And that was how I created one for him and I was like, why don’t I just create a blog and put all of this information that I have. So I started doing that.

I did that for four years before I then got employed by the largest tech blog in Nigeria at the time, Mobility Arena. So I became a senior editor there for two years and then I also did radio as well. I got the opportunity to have a radio show where I got to talk about tech and I remember our first episode being about Facebook buying Instagram for US$1 billion back then and d we lost our minds. We were like, how can you spend US$1 billion to buy Instagram? Like, a photo app? So I remember being very passionate talking about that acquisition back then, that was my very first episode.

I got to do radio for a year and a half before I then travelled here to Malaysia and I’ve been blogging for like seven years now, I’m tired, I want to do something different. So I tried video, which prior to coming to Malaysia, I’ve only held a digital camera once in my whole life, so I didn’t know anything. One day, in the middle of the night, I took all my money and I bought a super expensive gaming laptop at the time, which was about RM6,300. It’s US$2,000 plus in 2014. That’s a lot of money. So I got home that night and I was like, hey man, are you stupid? How do you spend this money on gaming? What? That’s not you! I think that cognitive—I was trying to like, you know, cognitive dissonance myself into: This is why you bought the gaming laptop, right?

So I called my friend Shruti. I said, “Hey Shruti, you love me, right?” She said, “Yes, I love you, Emmanuel.” “Okay, if you love me, then you’re going to lend me your camera because I want to shoot my first YouTube video.” I took the camera and I kept on flipping the dial until I saw something that did not look like total rubbish and I was like, okay, yes, here we go. And that was how I started my YouTube channel, and seven years later, shooting over 500 plus videos, covering about 150 plus brands, working with some of the top brands that I would never have imagined like Acer, Asus, Samsung, doing lots of branded videos for them, and going on a totally different journey.

So it's quite interesting because when I was in Nigeria, my blog was the Emmagination, E-M-M-A-gination—so a play on my name, Emmanuel, and the website was justemmagine.com. So I was known as Emmagine back then, and then when I came here I was known as Geekception, and now there’s sort of like a third rebrand where I’m Captain Awesome now, where I am doing more lifestyle kind of videos with my running, with my intermittent fasting. So I started a YouTube channel last year where I decided I’ve been running a lot, I had a challenge to run 1,000 kilometres last year—I did that.

This year I said, higher! More! So I was like, okay, I’m doing 2,000 km this year. Yeah, so I started my own channel, Emmanuel Olalere, my own Captain Awesome brand, which is just sort of an evolution of my creative journey where, before it was just quantity, like lots of videos. I think there was a time in 2017, I believe, or 2018, where I uploaded a video every day for 55 days. So it was—it was an experience, I would not recommend it because basically, I had no life. That is not sustainable forever, right? So, growing older, having different priorities, even growing as a creative as well, to sum up, quantity gives you the opportunity to discover your taste. So then when you discover your taste, then you can use quality to sort of refine it.

TINA CARMILLIA: I will come back to your running, and your nutrition because those are pretty high tech, especially because it’s coming from you, a tech geek. But we’ll come back to that. So recently Apple had their Worldwide Developers Conference. I saw you tweeting a little bit about it. Do you want to summarise, a little bit your thoughts on it?

EMMANUEL OLALERE: There’s positives and negatives. Positive in the sense that Apple keeps driving privacy in a world where it seems that everything is being spied upon, where everything is being misinformed, disinformed. So Apple is, I think, in many ways—charged a premium for it, let’s not confuse that—but provided tools that have enabled your data to be your data, at least, compared to the industry, to Google.

Definitely, with the Worldwide Developer Conference, Apple was able to really make one thing, which is called private relay. Basically, it’s like a Tor process, where Tor is like a super private—even higher than VPN—security, when it comes to the Internet. But they’ve been able to take such a complex and very not so user-friendly process, and bring it into every iPhone from until seven years ago, which means that even an iPhone 7 or 8 would be able to have a secure communication that is double-blinded. And it’s even better in many ways than a VPN, because with VPN, governments can request for data, and they can strong-arm smaller VPN companies to hand over your data. But in this case, even Apple does not know what the data is, so I would say that’s a positive.

And the negative is that Apple still continues the very two-faced approach of where, countries like China, Russia, where stuff like that is still not available. This is in terms with how Tim Cook is gay but in China, they ban gay apps on the App Store, and you prosecute other people like that. It’s very two-faced in a way where, again, we come to the whole capitalism and all of that, and all of that. But, basically, it feels very off.

Another emphasis is in health though I think it doesn’t really apply to a lot of the world because to most of these tech companies, there’s nothing there. Of course, they released newer versions of their mobile operating systems, which—for the iPad, for example—was very controversial because they put this very super powerful—I’ll use an analogy that everybody can relate to, basically, you have Toyota Corolla body and then you put the engine of a Ferrari inside. So people thought, oh, it’s got a Ferrari engine, it must be fast. But the output is like, no. So there’s some controversy there.

Another key takeaway in the security part: I think with iOS 14 and moving on with iOS 15, which they just announced as well at WWDC, they’ve given you the ability to actually know what apps are tracking you. So this basically led to a huge fight with Facebook because Facebook tracks everything. So Facebook actually released a notification in their app on iOS like, hey, enable us to track you because this is how we keep it free. So it was like a thinly veiled threat.

So that’s a huge controversy as well but I think it’s a huge step in the right direction, not just for ads and privacy alone, but I also think it will affect content creation as well because the ad-supported services are free, right? So, basically, you are the product. But what happens when they can no longer track you? Then they have to actually charge you, right? And if they have to actually charge you, then it has to be worth your money for them to offer the services. So I think, maybe down the line, there will be a change to—even how Twitter right now is coming up with like the premium Twitter account, where you can say stuff—and there’s more of those. I think we’ll start to see more shifts industry-wise in that regard, where yes, we’ll pay more but again, are we paying more when we’ve already paid so much with all our data?

It’s very dystopian when we think about it so we don’t like to think about it, but I think there’s more sophistication with AI and predictive stuff, and we start to actually see the real impact of the amount of data these people have on us. And again, the US election was a huge example when Trump came into power with disinformation and how there was ultra-targeting. I think the more everyday people start to see that, hey, wait, wait, hold on a minute, if I’m the product and—wait, I’m more valuable to these people than they let on, right? I think there will definitely need to be a conversation—maybe it will not mean that everything will be paid for but I think it will spark a conversation in ways where it's like—hold up, you can’t do this indefinitely. Right?

And in many ways, Apple sort of cut the time that that was going to happen because, again, in North America, where Apple and most of the paying customers, or at least most of the customers that generate a lot of value—in the U.S., for example, if they can no longer track on iPhone, that’s a huge chunk of their actual, monetised customers. So, yeah, I would say Apple really quickened that process.

So, in response, Google also announced the same with the Android 12 operating system, where they said, yes, you have privacy. But then people were like, wait, hold on a minute. You’re the largest advertising company in the world. So how are you going to say, you can provide privacy when you can see everything? Like, how—isn’t that like a conflict of interest? So it’s very funny when Google tries to pull moves like that. But they are pullling moves like that, they have announced new features in Android 12 that are able to give you more privacy-focused features. For example, apps that have access to your camera, now, it's an opt-in, as opposed to an opt-out before—at least up until Android 10; Android 11 sort of changed that. And with Android 12 now, they are all opt-in, which means that you have to enable the app that yes, you can track me, which is crazy that is just now that it is happening, 10 years later when all our data is online.

In essence, WWDC has sort of been a shock to the system in just how privacy can really be brought to the everyday person, and I think it’s not going to change. The more people realise that hey, I’m the product? Hey, you’re doing this? You’re doing what, now? Yeah—I think it will spark that curiosity, where they’re going to be like, hold on. How much do you have? Wait, you have that much? Can you delete it? What can you do with it? So I think it will definitely spark that.

TINA CARMILLIA: Absolutely. So now let’s get a little bit more personal. Let’s talk about your activities, your fasting and your running, which you log online. Obviously, with that kind of information it's also, in a way, an extension of your personal data, isn’t it? It may not be the most personal information, it may not be your blood type or your address and all of that, but it still tells gives us an idea, for instance with your running, where you typically would frequent. So if I have bad intentions, I could be stalking you and pounce on you from the bushes as you run pass me.

EMMANUEL OLALERE: Been there, done that.

TINA CARMILLIA: Oh, no! Okay, so tell me more about it. Tell me how do you balance—I mean, it’s a form of accountability, isn’t it, when you log this information with your nutrition and with your exercise—how do you balance your accountability to yourself, maybe to your social group, and also ensuring your privacy and safety at the same time?

To be a cisgender male, where I don't have to face the challenge that, for example, people who identify as women will have to face when it comes to harassment—I'm lucky since I don't have to go through those experiences, but just because I don't go through them doesn't mean that I cannot acknowledged that those things exist. I may not experience those things because of the privilege I have, I definitely acknowledge and push for better moderation tools…because what is there right now is just pure rubbish.

EMMANUEL OLALERE: Balance is quite hard because we both know—I mean, most likely anybody reading your newsletter or listening to this know—that it is very hard once you’ve put something online to take it back. So, it has to be a very determinant thing. So, for me, when it comes to the content I put out, I really, really do agonise over stuff I put out. And if you notice, I’m not very personal personal online, which means that you’re not going to see my family, for example, on my social media feed. If I’m dating anybody, you’re not going to see it there. If I had a kid, for example, most definitely you’re never gonna see that there.

So, in many ways, I’m also quite conscious, in the sense that someone—for example, my ex had no Instagram account, no Twitter, no Facebook, which is very rare in 2021, right? She had nothing. She only had Whatsapp. To her, of course, I’m like the most open person online because I’m posting all those stuff, but for me, personally, I know there’s certain things I don’t post at all. In fact, this is the first time I think the public will hear it for a while but I make one-second videos every day. So I’ve been recording that for a couple of years now—that will never make it out. But you know, there’s so much more stuff that I’ve created than I’ve released. So, as someone who is a content creator online, someone who’s just online in general, I know how to be very responsible with stuff I put out. So, as much as possible, I try to put out stuff that I know that okay, if this was exposed, for example, or if this was taken into a different context other than the context in which I created it, will I be cool with that? If I’m cool with that, then I’ll post it. If I’m not cool with it, then I don’t post it.

And also, there’s digital hygiene, which means that when it comes to tweets from four years ago, five years ago, I usually run an auto-deleter that deletes past stuff because maybe they’re not the most representative of who I am now. I mean, we know the online culture that we have currently right now, which is that once you say something, that’s it! Even today, I was thinking about it. Most of us don’t have digital wills, right? Let’s say for me, as someone who has 12 Google accounts, payment accounts spread across Stripe, PayPal, this and that. I have my bank accounts, I have my robo advisors, I have so many things my family would never know about. There really should be a digital will where on my passing, all my passwords and all digital assets, I should be able to pass it on to someone. Maybe it’s a next-of-kin, maybe it’s a friend, it doesn’t matter who, so that it’s not just lost.

Imagine, there’s so many people online today where you thought this person just stopped posting but they’re dead. They’re no longer with us. It’s a very grim reality but it’s a reality, nonetheless. I think many of us never actually think of being able to let that data go, as well. Even for me, I’m an obsessive tagger, I tag stuff. I have second brain, I have an operating system of stuff where I have everything you need like my migration plans, my values, the stuff I’m doing, my monthly reviews, my quarterly reviews. You know when I pass—or even right now for stuff I have of other people, do they not want me to have it anymore? How does that work? So many complexities, I think maybe born out of the fact that we are still quite relatively young when it comes to the Internet, when it comes to actually being able to handle all these zettabytes of data that we have created. So now it’s like okay how do we sort through all the data, how do we categorise it, how do we sunset what we’re supposed to sunset, right?

For me, it’s still very much a learning process when it comes to thinking beyond where we are now. But currently where we are now, it’s still when putting anything out there, it is with the full consciousness that it is out of my hands. In many ways I can consider it a locked. To be a cisgender male, where I don’t have to face the challenge that other people, for example, people who identify as women will have to face when it comes to harassment, sexual harassment as well—because I manage my sister’s Facebook for like the longest time, because again I’m the tech support guy. Even up until seven years ago, there was so much unsolicited photos of genitals. There’s so much harassment when it comes to men demanding my sister’s attention or time.

I'm lucky since I don’t have to go through those experiences, but just because I don't go through them doesn’t mean that I cannot acknowledged that those things exist. There should be better tools actually moderate content like that. So, for example, when they don’t fit into the standard body type, they get it even more, right? So it’s like, apart from, okay we’ve let it out there, I really believe that there should be a way for the platforms to do something about it because definitely it’s lacking. And I have seen my friends mental spaces collapsed just because some random person sent them some message that was just uncalled for. So, yes, while I may not experience those things because of the privilege I have, I definitely acknowledge and push for better moderation tools and better punitive measures for people who violate those rules and most definitely, it’s something has to change apart from what it is currently because what is there right now is just pure rubbish in many ways.

Ad-supported services are free, right? So, basically, you are the product. But what happens when they can no longer track you? Then they have to actually charge you, right? And if they have to actually charge you, then it has to be worth your money for them to offer the services. So I think … we’ll start to see more shifts industry-wise [towards premium], where yes, we’ll pay more but again, are we paying more when we’ve already paid so much with all our data?

TINA CARMILLIA: You’re right in saying that, actually I don't know much about you despite thinking I know a lot about you based on our online relationship, which is not something that I could say to a lot of my other online friends. I actually do know a lot about themm and their family, and their friends, and their history 10 years ago.

As an online creator, I think you create this parasocial relationship with your audience and we feel like we know you really well, but you also—because you’re such a tech savvy person—you’re able to guard your most private, most personal information and keep that just for you and those that matter to you and I think that that’s something that a lot of us should be more mindful of when we do anything online or offline, in fact, right?

I want to know your thoughts on the MySejahtera app. Tell me the dirty details, what do you think of it?

EMMANUEL OLALERE: So, I’m not going to get deported, okay?

I’d say the concept was a good idea. It was a good idea, theoretically—an app that is able to provide you updates, you are able to see status around you, to vaccinate yourself, to check what is the latest news going on, you’re able to—it sounds great, right, it sounds like something where you sit in a boardroom, you’re like, yes, do it! That is, a million dollars, here you go, right? Or in this case...

TINA CARMILLIA: RM70 million... (Ashman Adam, Malay Mail)

EMMANUEL OLALERE: (Laughs) Right?

So it's a great idea... In practice, though? Not so much. And again, as someone who knows the tech part of it, because I used to be a developer, so many of these things I actually know what the backend is like. It does show it’s very ill-prepared. On the frontend, it looks competent enough, it’s not a bad app, right, but on the backend, it’s definitely symbolic of many things that we’ve noticed in this pandemic, right?

We might intellectualise a whole lot of this over podcasts, over calls, over Twitter, but the reality is these things affect real human lives. And if there’s one thing that I’ve learned as a Nigerian who lived, and grew up in Nigeria, I’ve learned to see dysfunction firsthand. I grew up in a country where we had to provide our own electricity, we had to dig our own boreholes or our own wells, so a well or a borehole is a common sight in almost every home in Nigeria. We have to pave for our own roads. We have to build our own schools. We had to do everything for ourselves, basically, everything. Everything. The government doesn’t do anything for us.

So, in many ways I know what dysfunction, feels like, at least on a Nigerian level—I cannot hold an exclusive right to dysfunction—hence why I’m no longer in Nigeria. But coming to Malaysia, and it’s quite—again, for me, as someone with that context and with that background—it is quite sad to actually see the dysfunction happening here as well, because when I came here to Malaysia in 2013, it was with so much hope and so much glimmer—and okay, I was 21 also, so I was young. But you know, the hope was there nonetheless, because Malaysia held what Nigeria never was.

In Nigeria, I’ve never had 24 hours of electricity for 21 years of my life, which means that I lived in Nigeria for 21 years and I’ve never had uninterrupted power supply. I came to Malaysia and there’s uninterrupted power supply. Internet service was so bad—and I know in some parts of Malaysia it’s like that, too, right, but in Nigeria, even in the cities it’s like that, which means that I had to have four different phone lines, because at different times of the day, let’s say if you had a mobile network—in the morning it will work perfectly fine. And then when it’s 12 p.m. we’ve got to switch the line to another line. So, you can imagine how it is as a creative person there, where you have to maintain four different lines, and there’s no guarantee they’re gonna work.

Imagine in 2021 or 2020 where we have the pandemic, everything has shifted online. Imagine how creatives back there are having to cope now because it must be hell, right? And that’s on top of no power, which means you have to provide your own power around the clock, which means that there’s a lot of noise pollution because there’s generators everywhere. There's a lot of pollution pollution because there’s a lot of pollutants from those generators everywhere.

You know, back home, if we are travelling, we pray, you know, we literally pray, we’re like, “God is going to guide you. You’re going to get there safe.” And I came to Malaysia and it was a huge culture shock because nobody prays when you travel, and I was like, “What is that?!” You just go there! So Malaysians don’t even need to think about safety because you’re safe. When you’re not safe, it makes the news, it’s like national views.

So when I came to Malaysia, there was a lot of hope and I’ve been able to capitalise on the hustle that Nigeria gave me because there was just so little. When I came here and I'm like, you mean I can just do something and people would be like, “Okay cool, take more”? And that’s how I was able to build my YouTube channel and that’s how I was able to reinvent myself.

I would not say I was an A-class celebrity or a B-class celebrity but I was a C-point-D class celebrity back home where people recognise me and I came to a new country where nobody cares at all and it’s like, I’m totally anonymous. I really worked hard and one thing I notice here is due to the chill nature in Malaysia, I was able to really make a lot of progress because many people would be just like, “Yeah, no, I want to go eat lunch now so I’m gonna go,” but for me I don’t eat lunch, I don’t eat breakfast. I barely even eat dinner because I was like, so poor back then. There was only one thing on my mind: Just create stuff, create stuff, create stuff.

I remember coming to Malaysia with just US$100 for five months. Even when I started my YouTube channel, for two years I only ate bread every single day. I have a container now that has all the bread tags that I get for two years, non-stop. I could do that but like another Malaysian in the city where I stay here is not going to do that because, “Oh, my god, I’ve not had my breakfast, the world is going to end.” So I was able to take advantage of that. That’s because Malaysia was a good enough place to do that.

Now coming back to the reason why I went into all my backstory is that I’m starting to see a lot of that dysfunction seep into Malaysia as well. For me, it’s actually not a happy thing. When I see it on Twitter, when I see the politicians make all these outlandish statements? Yeah, it’s the same thing back home. Malaysia is at the point where Nigeria was in the 80s.

Nigeria in the 80s—our currency was better than the British pound. Immigrants used to come to our country to come work because our country was such a high-value country. We had so many people travel abroad because it was actually cheaper to study abroad because our currency was so good. [We] go from that to where Nigeria is now where we have a diaspora population of more than 15 million outside the country, where most of us don't want to go back when we leave, the government even worse than they were when I left, inflation at such a high—when I left the country US$1 was ₦150, now US$1 is ₦600. When I came here, my mom could send me money and I could pay for four subjects, but two years later, I could barely pay for one subject and eventually I could not pay for any subjects at all.

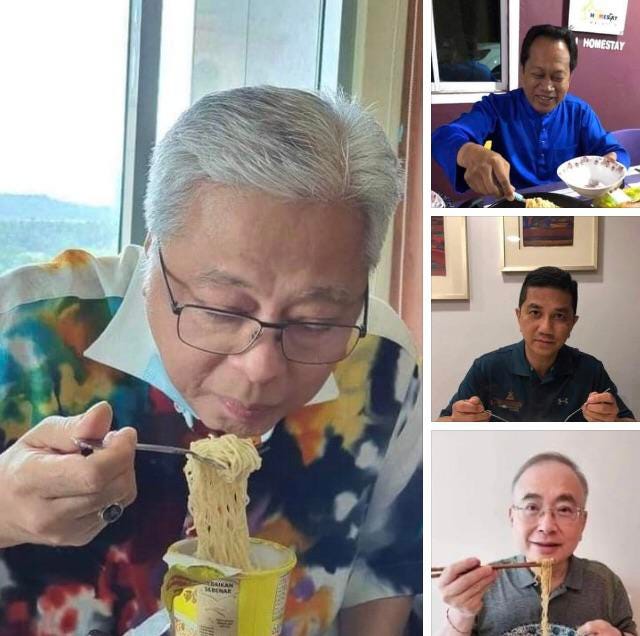

In Malaysia, I’m starting to see similar patterns, and when it comes back to the MySejahtera app, I think it’s just like a greater, deep connection of just how dysfunctional things have gotten that this is normal now. It's not outrageous anymore and it’s the normalisation that gets to you, right? It starts very small and before you know it, it’s the bare minimums, and before you know it, it’s even worse, and that’s why all of a sudden, [politicians’] photoshoots with Maggi is like the new in-thing, right now, right? It’s like, “Oh, we’re one of you,” but not really. These things? Yeah, we saw it too. For me, it’’s like deja vu. And I’m like, this is how it started. It’s so scary, it’s like PTSD. I’m like, okay, escaped Nigeria. And I say, oh my god, no! No!

Like the clamp down on foreigners? You know, fun story—not so fun story. In the 90s, Nigeria actually expelled Ghanian citizens. They said, hey, all, Ghanian citizens, we’re tired of you. It’s first xenophobic, right? We’re like, we’re tired of you, come, leave our country. That’s not all. We told them to leave, and not only that, we named a bag after them leaving. So the name of the bag is called Ghana Must Go because we gave them that bag and told them: Ghana, go. It’s not only bad that we deported them. We also named a symbol, a bag, till today that bag is still called Ghana Must Go.

So when I see stuff happen here with migrants from countries that are not white, I’m like, wait, hold on. When I see a deportation of someone who’s being overly critical? Same playbook. Same playbook. It’s actually quite sad because I believe in the potential of Malaysia. If Malaysia were a country where I could attain citizenship, a country where I could get the opportunities that is not segregated according to my race or according to being a foreigner, I would in a heartbeat. What am I looking for? The weather is great, the people are great, the food is great, I mean, I love pisang goreng to death. I would, you know? But it’s so frustrating that there’s a huge disconnect between the ruling class, and then the common person on the street, right? There’s a huge disconnect and in many ways, I think MySejahtera is a perfect example of that disconnect.

TINA CARMILLIA: Yeah, I’m glad you brought up Nigeria quite a bit because I’m wondering if you have any thoughts about Nigeria, banning Twitter. Is it still banned?

EMMANUEL OLALERE: It’s still banned.

TINA CARMILLIA: What is happening, I mean Nigerian Twitter is fun. Now I’m like, where’s the Nigerian content?

EMMANUEL OLALERE: It is, it is so fun, yeah. But I guess it’s just a combination of the rising authoritarianism in Nigeria, and also the rise of the same things we are seeing, almost the world over, right? It’s the other people, it’s the migrants, is the other tribe, it’s, you know, it’s ‘The Others,’ right? And it’s quite ironic because in Nigeria, the people who feel under threat the most are the people that have the most government seats, right, the people that have the most states.

So, sounds familiar, right? Exact—that’s what I'm saying. It’s like a combination of all that and I think we spoke about how the Internet is a leveller. Perhaps the Nigerian youths or the Nigerian populace had levelled too much with the Internet so they were like okay, if they don’t have this platform—because you know, many in the older generations like to berate the younger ones. But time and time again, we have seen how movements have started from niches, corners of the Internet, but they’ve spread very much to the everyday reality, whether it’s here the yellow protests that had happened over the years until the government actually changed—all of that were all mobilised on the Internet; whether it was back home, where we as Nigerians have a perception of ourselves as very disorganised, very corrupt. We have the self image of ourselves—we’re very docile, we don’t do anything.

And during the End SARS protest, which was a protest against an arm of the police that had and continues to harass younger people in the country, everybody just through the Internet and from Twitter specifically were able to mobilise. When people got arrested there were lawyers on Twitter, they were able to mobilise other lawyers to bail them out. When people needed money, they were able to raise about, I think, in excess of US$6 or 7 million. Not only that, unlike a traditional political project, it was very transparent. They release all, to the last cent—accountable for every single thing. They hired a third-party auditor to audit them—two third-party auditors to audit them. The movements were led by women back home. The main faces of people who actually did a lot of stuff were not traditional leaders in the Nigerian context.

So it broke a lot of preconceptions that we had about ourselves. We always think we are very dirty, we’re not clean. People actually brought brooms to protest on the street and clean up after themselves. And I was like, what? It was very surprising for all of us and I think it really spooked the political class back home that they really got scared like, oh damn, this is possible? So this was a response to that, which meant that there is change from online platforms, right?

Even when my mom who told me 10 years ago, “Emmanuel, why are you spending so much time on the Internet? You're just spending all my money, buying Internet data. Why are you doing all this?” For me, I’ve always known the power that being online gives, in the sense that it gives so much possibilities. If you need to find something, if you need help somewhere, you can just tweet it out and people will help and it’s very quick, very fast, it’s free also.

So I think the political class in Nigeria, as a result of that— and we don’t have a Sedition Act in Nigeria, that was lifted a while ago and they’ve been trying to sneak it back, it’s not like they’ve not tried, but they’ve not succeeded. So it’s illegal what they did by banning Twitter but they banned it anyway because we live in Nigeria where there are no rules, yeah, so in many ways again, coming to Malaysia, we’re starting to see heightened prosecution of different figures that don’t toe the line or don’t keep quiet or don’t follow—okay, don’t complain too much about it or just don’t make too much of a ruckus. Yeah, you can complain about it but complain among your tiny, little friend circle. Don’t come online here and make some seditious statements, you know? We’ve started to see a rise of that not just here but in India as well. India is also mulling Twitter ban as well. We’re just seeing that authoritarianism because, why not, right? Why not?

TINA CARMILLIA: Alright, so let’s take a pause here and we’ll come back with more of my conversation with content creator Emmanuel Olalere, where he’ll let us know what it’s like to be a tech reviewer and how discrimination plays out in the wider tech industry. All that on The Starting Block next week.

Meanwhile, if you would like to join me for conversations like this, get in touch here.

Don’t forget to subscribe, if you haven’t, and if you enjoyed this episode, consider sharing it with someone. ‘Til the next one, goodbye for now.