The Sidelines is the supplementary issue to every main edition of The Starting Block. Here you will find the full interview and more information about the conversation of the week. The interview is edited for length and clarity, and all links provided come from me, and not the guest.

This is a text-only conversation for this week’s newsletter.

TRANSCRIPT

TINA CARMILLIA: Now, in the next lane: counterterrorism analyst Munira Mustaffa. Our topic this week: online deception – Katie Jones, and beyond. Ready? Let’s go.

Share with us a little bit of background on your work leading up to the discovery of Katie Jones, which we will touch on in greater detail later in the conversation. For now, what have you been up to these days, professionally?

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: I have been working as a counterterrorism analyst since 2016 within the private, government and military sectors. In 2018 – 2020 I was attached to American University in Washington DC, and now I have returned to Malaysia where I work within the defence industry. I am also a Verve Research fellow.

TINA CARMILLIA: “The camera doesn’t lie” no longer holds, even before the case of Katie Jones, the senior researcher at a DC think tank who does not exist. So let’s look at the history of old-fashioned photo manipulation before moving on to deepfake and generative adversarial network (GAN).

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: The principles of deception are eternal. It’s always worth remembering that deception, disinformation, fakes news, hoaxes, propaganda, etc. are not new phenomenon developed by technology. Technology merely assists their relentless and persistent presence because they make creating a story, narrative or message to be convincing for deceiving, misleading or influencing the intended target, the audience.

Disinformation and propaganda have a long history since the birth of civilisation – they were instrumental in altering public perception of political campaigns, eroding the legitimacy of rulers, and even demoralising the enemies to direct war efforts. The invention of photography also prompted opportunistic people with talent or specialist skills to be creative. The effort to edit and manipulate audio, video or still images used to involve literal cutting and pasting, slicing and splicing with a scalpel, razor blades, sticky tapes and glue.

These days, you simply use any apps on mobile phones – they are widely available at the literal fingertips, and they are faster, cheaper and easier. Anyone can use them without requiring artistic skills.

TINA CARMILLIA: Share with us a little bit about your tools and methods in the case of Katie Jones.

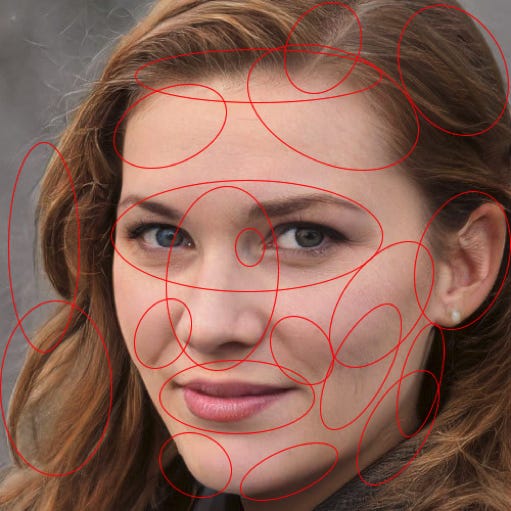

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: I simply performed open-source intelligence (OSINT) work to investigate Katie Jones. I saw that other than her LinkedIn, she had no other presence or publication evidence to validate her existence at the organisation she claimed to be working for. It was her profile photo that did not sit well with me. I thought it was a stolen image at first, but a reverse search showed no results. The question I was asking myself was, how do you have a photo that looked like it was professionally taken without a digital footprint if the person was not real and the photo was stolen? I could not understand it at all. It was not until I took a closer look, that was when I started to notice what was abnormal about the photo. For one thing, there was a gaussian blur on her earlobe. Initially, I thought she had her earlobe photoshopped, but that made no sense to me because why would anyone photoshop her earlobe?

Once I started to notice the anomalies, it was like everything suddenly started to click into place right before my eyes. I immediately realised with a shock that what I was looking at was not a photoshopped photo of a woman. In fact, it was an almost seamless blending of one person digitally composited and superimposed from different elements. I immediately recalled that I had read something about this on a Twitter thread just the week prior, so I went back on Twitter to dig up the thread. Pretty soon, I was reading up about GAN. I went on thispersondoesnotexist.com and started to generate my own deepfake – one photo after another. After scrutinising about half-a-dozen deepfakes, I started to pick out the patterns and anomalies in every single one of them, and I went back to Katie Jones to study it further. Sure enough, they were all there.

TINA CARMILLIA: And when you made the discovery, did you realise what was going to be its implications?

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: To be honest, when I provided my assessment on Katie Jones being a deepfake, I didn’t realise it was going to be a big deal. As it turned out, I had somehow stumbled upon a hostile state effort trying to worm their way into LinkedIn to map out the network of security and defence professionals on the platform. It was only later I realised that we had uncovered the first documented instance of a whole new method of deception, that has now become mainstream and a serious challenge.

TINA CARMILLIA: The reporting on Katie Jones was made just under two years ago. How much has changed since, in terms of how the intelligence community treat the threats of sophisticated ruses like this?

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: I cannot speak for the intelligence community at large because it is a very diverse space. Also, different countries respond to varying level of threats very differently, depending on their prioritised needs.

The way social media platforms engage with security threats also depends on their regional engagement strategies at the country level. Back then, a lot of the effort was focused on targeting Islamic State messaging and propaganda and deplatforming their members and adherents. To an extent, that was immediately identifiable and straightforward because IS are non-state actors.

But when it comes to disinformation threats, that’s where it can get nebulous because of the political nature. It really depends on how different governments define what is disinformation, and social media platforms will have to redefine their policies in response to their stakeholders. Some states are even responsible for generating disinformation themselves because cyber is a competitive space for powerful state actors.

TINA CARMILLIA: And do you find that the public has since become more aware of, more cautious of deepfake technology or are they unbothered, maybe even desensitised to it?

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: I think the public is certainly more aware of the presence of deepfake now that it is being commercialised through fun vanity apps such as FaceApp. That means that when people encounter networks of deepfake-enabled bots on social media, it is easier for them to realise what they are seeing. But it is also difficult for the public to exercise caution because we are being overwhelmed by so many overly filtered photos.

At the same time, people do care about authenticity – but that would also depend on their framing of what is considered to be truthful. However, with that said, I am also deeply apprehensive that the fears around deepfakes have been exaggerated where state-sponsored disinformation are concerned.

TINA CARMILLIA: And the way governments and social media platforms respond to security vulnerabilities and disinformation threats?

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: I think people still have trouble differentiating between the impact of regular disinformation and cheapfakes. It is worth mentioning that the first use for deepfake was to harm and malign women to create fake pornographic products of them without their consent or even revenge porn. Unless deepfakes are properly backstopped, in terms of state actor warfare, deepfakes are not really worth the effort and can be debunked. In comparison, cheapfakes are easier to produce and more effective.

TINA CARMILLIA: Briefly on the distinction between malicious actors that are part of a coordinated, targeted state-run operation and lone individuals – is it helpful to make such a distinction or should they be treated the same?

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: Distinction is very important because we need to give the appropriate response in countering the threat. You cannot and should not give blanket treatment to state and non-state actors. They are not the same thing. You’d want to be able to use the relevant tools, techniques and expertise to deploy capabilities to counter the pertinent threat. It’s especially challenging now that the tools to create these campaigns are so cheap and widely available – so not only lone actors but also commercial enterprises can create deceptive campaigns that effectively work in exactly the same way.

TINA CARMILLIA: And do threats like this matter more to bigger, powerful countries like the US or the UK and less to smaller ones like Malaysia and our regional neighbours? Should we care as much, do we have the resources? (Or are we, like North Macedonia, a training ground for larger targets?)

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: Just because we are less powerful, and may have fewer resources, does not make our population a less attractive target for malign influence by hostile foreign powers or even by unscrupulous domestic operators. But we can learn from foreign experience and apply best practice observed abroad, especially to avoid some of the major mistakes the big players have made.

TINA CARMILLIA: On the subject of LinkedIn – do you think it is not getting enough scrutiny compared to other social media platforms e.g. Facebook, Twitter, etc. where deception and disinformation campaigns are concerned?

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: The nature of LinkedIn, and its model of connecting and endorsing profiles, means it presents a particular challenge. But it would be a mistake to focus on just a few platforms instead of treating this as a holistic problem across the board – because that is how our adversaries see it.

Cheapfakes are less sophisticated and less polished than deepfakes, yet they can cause equally damaging outcomes.

TINA CARMILLIA: Extending to the present day, how much more sophisticated are these techniques, and what are the available countermeasures?

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: Deepfake technology will continue to improve, but we should not be too preoccupied with worrying about deepfakes causing disinformation, sowing misinformation, causing political damages or disrupting elections. Cheapfakes are less sophisticated and less polished than deepfakes, yet they can cause equally damaging outcomes. These products are only as effective as their user manipulators can make them.

What matters is how they are being deployed, and what kind of narratives are being fabricated to accompany them. We just have to accept that deepfakes and cheapfakes have become part and parcel of cyberspace and of deception – what is critical is acknowledging that there will always be newer technology being developed that can be used against the public.

Relying on technology as a solution to address these problems is going to be limiting. What is useful to counter these problems as threats is being able to identify who are the most vulnerable members of society that these can be used against, and formulate practical policies and social solutions that can increase public resilience and improve awareness and literacy.

TINA CARMILLIA: And if we can’t believe everything we see, can we believe everything we hear? Perhaps you could share a thought on the recent boom of the digital audio medium.

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: AI voice cloning has already existed for a while now and research on audio deepfakes were already underway for a few years now. And yes this is an area where deception can be practised against the unwary with potentially very severe consequences, as we detailed in the Katie Jones report. But that’s not the only problem. Several people have already voiced their concerns on the regulation and moderation of spaces like Clubhouse.

TINA CARMILLIA: And lastly, some advice or outlook for the future.

MUNIRA MUSTAFFA: Deepfakes are here to stay, with the convincing generation of completely artificial images, video, audio and text. But we shouldn’t get too fixated on the technology. It’s the underlying principles of deception that malign actors consistently leverage to harm our people, our governments and our societies. So it is the intent behind the deception that we need to address in order to safeguard all of these things.

Technologies for deceiving us will continue to emerge, and so will countermeasures for them: the one constant is our need to be on our guard and to protect the most vulnerable and easily led astray among us.

TINA CARMILLIA: That’s Munira Mustaffa, counterterrorism analyst on the threats of online deception.

If you would like to join me for conversations just like this one, get in touch here. ‘Til the next one!

boleh tahan jugak lah anak malaysia not bad sis

I come here after seeing the press that she made recently. I find her a very good commenter and good luck for futre